Film Quarterly Reloaded

If you haven't yet checked out the new Film Quarterly site, do so. It's not only pretty to look at, it also bears the promise of becoming a genuine online resource, site of good arguments, archive, more. Here's hoping...

That, and the new issue is killer, for a number of obvious reasons.

A moon made of fish, a dog made of horse hair, a skull made of beetles that eats the white bird

Needless to say, if you're in NYC, go see the Dead or Alive show at the Museum of Arts and Design and behold.

Fecund revenge: green Geist screws us all

[excerpt from Combined and Uneven Apocalypse, taking on Swamp Thing, scarcity, and "green politics"]

One of the other strengths of Life After People, beyond the genuine pleasure of its recurrent apocalyptic money shots, is its awareness that the processes which unmake the world after people are already taking place. If it refuses to ask how we disappear or how our disappearance would necessarily shape the world left behind, the series makes clear that it takes a constant work to prevent life after people from commencing while we’re still around. Cities may be “third nature,” but that doesn’t stop “first nature” from waging constant war. The battle for the post-human history of the earth has been going on all along from the moment that human history started.

If not the best known, then certainly one of the most compelling (and internally inconsistent) articulations of this is the long running DC comic book series, Swamp Thing.

The sheer breadth of histories and trajectories involved in its story arc are obviously beyond my reach. Of immediate relevance here are two particular moments within Alan Moore’s run as author of the series, set against the general backdrop of Swamp Thing’s “evolution.” The story of Swamp Thing, at least in Moore’s version, is the story of a transition from singularity to universality. It is the transition from a swamp monster (dead scientist recomposed by the nutrient force of the bog) to the fecund Thingliness of all plant life (green elemental force itself, not bound to any particular configuration of matter but rather the abstract Geist of flora). Hence the multiple revelations of the series. He realizes that he isn’t Alec Holland with a plant body, or even the Swamp itself with the injection of a consciousness defused into it. He isn’t even the Swamp Thing: he is one among a recurrent series. He is the idea of the Green, the collective chlorophyllic intelligence of what lives but is not Meat.

He’s also a total hippie hero, Platonic vegan ideal incarnate, complete with mournful eyes for the blighted earth and psychedelic tuber-tumors for inner light exploding acid-trip sex. His consummation of “relations” with his girlfriend Abigail starts with her eating one such tuber and then spreads over multiple pages of pastel light, chakra symmetry, suddenly understanding time itself, and becoming-Oneness. It well may be the world’s most concentrated distillation of New Age ideology. However, just as the end of the ‘60s brought out the seedy and sadistic undercurrent of hippie-dom there from the start, it is this consequences of this trippy bedding-down – free love and ecstasy beyond the need for fucking itself! – which brings his verdant fury to its full antagonistic flowering. It is the moment when care for the earth becomes notably decoupled from care for the human, when protectors of the Green reveal that they are no better at understanding the dialectics of society and nature than the arch-defenders of capitalism.

After a snooping reporter catches their boggy tryst, Abigail is jailed for “unnatural relations” and eventually winds up in the jail of Gotham City, beneath the watchful eye of none other than Batman. Swamp Thing, off dealing with other more literally infernal threats to the earth, learns of this, goes insane, and, manifested in a strip of green cutting across the enclosures and divides of pastures, roads, and buildings, makes a bee-line towards her. The eventual narrative outcome of this – he gets her back, he is “killed” and his consciousness escapes across the universe, and he works his way back – is not particularly relevant here. The point is what happens before: his revenge is the total halting of capitalism and previous modes of daily life in Gotham. It becomes a veritable Garden of Eden, and the hippie population of Gotham, surprisingly not previously eradicated by the rather straitlaced Batman, sheds their clothes and enclosures and goes back to nature in the heart of the metropolis.

Like so much of apocalyptic fiction, the structural is only approached through the personal, and so while Swamp Thing himself folds in plenty of claims about how humans act like they own the earth they mistreat and how he won’t take it anymore, the fact remains that this elemental force has known about this general mistreatment for quite some time now. A protector of Gaia, perhaps, but in this case, the rage and puissance boils over because of the mistreatment of a far more particular woman.

This is no accident of bad writing. Moore’s subtlety, or at least what saves him from total devolution into the mediocrity of animist post-’60s thought, is in the recognition of the persistent intersection of the concerns for the personal and the planetary. If anything, the baldness of Swamp Thing’s motivation is refreshing: it makes exceedingly literal and epic the ways in which worries about sustainability and protection of Mother Earth are not infrequently worries about the future possibility of getting laid. Less refreshing and more simply disturbing, in its implications for a type of thinking we recognize far beyond the DC universe, is the concluding gesture at the end of Moore’s run.

Having returned to earth, dealt necessary revenge to those who booted his consciousness off the planet, and reunited with Abigail, it’s time for general reflection on his realized position as elemental force. He has discovered, both in his shaping/pseudo-impregnation of entire planets elsewhere and in his Edenic punishment of Gotham, that he has the full capacity to radically alter the material conditions of a landscape. Hence he wonders, given this power, if he should make the world bloom in full, make it a green, lush environment, to end hunger and strife by eliminating scarcity itself? More than that, to reverse the damage of pollution and to “heal the earth”?

He decides otherwise. On one hand, this is entirely understandable, even for a green elemental power (supposedly) concerned with the defense of the planet. If the ravages of capitalism were not a necessary solution of scarce resource management but a contingent situation made into global order of mismanagement, it indeed follows that unbound plenitude will not necessarily result in things getting better. The infinitely adaptable forms of consumer identity prove, if anything, that the distance from our “natural” species-being to “second nature” knows no bounds. As such, from a historical and materialist perspective, it not only makes perfect sense to grasp that while plenitude and equal distribution is a goal of all egalitarian politics, it does not produce such a politics.

However, Swamp Thing’s reasoning is entirely opposed to this, arguing essentially that because humans have always dominated the earth and “taken it for granted,” simply providing the end of scarcity will not cause them to learn their lessons. They will profligately squander the new fruits of excess, reject all sustainable modes, and continue to wound an earth that now can bounce back from anything (like the sadist fantasy of a body that endlessly self-heals). His solution instead? Humans need to learn to take care of the earth themselves. He will not intervene – they will have to see how they are destroying their precious resources in order for them to change their ways.The cynical ugliness of such a position is unmistakable and would be laughable if it didn’t capture so much of the tone of green movements at their worst.

In short, this God-like defender of the earth is dooming it to catastrophic destruction. To sketch it quickly: humans “mistreat” the earth either because they are “just like that” (i.e. transhistorical human nature), or because their historical situation has conditioned such behavior (i.e. historical second nature). Obviously, the flimsier versions of contemporary ecological discourse fall back on the former conception of “civilized man” as the raping and pillaging animal. Even a cursory glance at prior historical modes of the reproduction of life make evident the uselessness, analytically and especially politically, of such an argument.

Taking on the second notion, then, Swamp Thing is caught, thorny brows knotted, between two models of how we learn to act a certain way. Do we act badly because we face fundamental scarcity and have to do whatever it takes to survive in the immediate, sustainability be damned? Or do we act badly because there hasn’t been enough scarcity, hardship, or antagonism? Outside of the Swamp Thing world, our answer would be: both/and. Those responsible for the worst treatment of the world and its human occupants continue to do so because we don’t make things hard enough for them: a little hardship and directed antagonism toward the rich is long, long overdue. At the same time, though, we know very well why such a mass uprising and tidal shift remains difficult. Those who most feel the brunt of scarcity and immiseration are so busy struggling to survive that the historical capacity to act otherwise – either in terms of directing antagonism toward those most responsible or in terms of living more “sustainably” and not participating in the mistreatment of resources – remains a dream primarily for those with the leisure time to imagine it.

In terms of the comic’s narrative, Swamp Thing refuses to recognize either position. Given his peculiar talents, we could easily imagine a mediated form, directing edible flora to areas of the world facing total starvation. But no. He essentially commits to perpetuating a contemporary order in which the problem isn’t just that we face ecological catastrophe. The problem is who it will affect first. (Hint: those already living below the poverty line, those packed into cramped and disease-ridden slums, those in areas barely surviving on monocrop production dependent on particular weather conditions, those in shanties that won’t stand up to tsunamis, those in zones of the world so ignored that no number of liberal guilt donation boxes in Starbucks will change a thing.)

Again, to draw out a now expected point, Swamp Thing’s refusal to be the apocalyptic force that he has been all along is the total commitment to total catastrophe. If he’s worried that making the earth full of food and lush green bedding will allow the thoughtless to litter and chemical plant capitalists to dump their waste in rivers, then punish them. His vegetal powers are not just regenerative but directed: why not be the proper growing eschaton, giving the righteous fruit to eat while lashing the wicked to tree trunks?

The only answer can be found in his deep anti-historicism and a fundamental hatred of the human animal – conceived as bad, across time. This rears its head continuously in the degradation of “Meat,” of all things red as opposed to green, of anything that consumes something else, not just humans. (See here his entirely unnecessary torturing of an alligator in the final pages, immediately after his meditation on treating the earth better.)

Folded into all this is a valorization of laboring itself, assuming that man will become wicked if he does not have to toil. And in line with this, how exactly does he propose that the human species will deal adequately with its already dire ecological situation? The only situation we see endorsed is Abigail’s participation in a tiny environmental group, i.e. her transition from literal lover of this defender of the earth to a somewhat hesitant love of earth defense causes. The scope of this group, whose numbers are slim to none, seems closer to letter-writing and pamphleteering. Furthermore, after his decision that the urgent situation of the polluted earth is to be dealt with by this second rate Sierra Club, of which Abigail is one of the only members, he whisks her away via lily pad to their flowering love nest built in the swamp for a couple months of gazing into each other’s eyes and hippie sex.

I’m no great analyst of what should be done with what is indeed a dire situation. But it’s no great task to recognize that putting the future of the earth in the hands of a couple activists before stealing one of them away for a secession-from-the-world honeymoon is more than just a failure. It’s atrocious bad faith in a leafy mask. It’s what follows from forging an eternal divide of the green and the red. It’s a damnation of us all. And frankly, we’re screwed.

What the eternal bells were saying was the same as what the books and newspapers wrote about, what the music sang about in the night-time cafes: "Waste away, waste away, waste away!"

A stranger to all thought, indifferent, as if he did not exist, Lichtenberg walked up to the radiator of the truck. The metal gave off a trembling heat; thousands of men, converted to metal, were resting heavily in the motor, no longer demanding either socialism or truth, sustained by cheap petrol alone. Lichtenberg leaned against the vehicle, pressing his face to it as if to some fallen brotherhood; through the chinks of the radiator he saw the mechanism's tomb-like darkness, in its clefts humanity had lost its way and fallen down dead. Only now and again amid the empty factories could you find mute workers; for every worker there were ten members of the State Guard, and in the course of a day every worker produced a hundred horsepower in order to feed, comfort and arm the guards who ruled over them. One miserable labourer maintained ten triumphant masters, and yet these ten masters were filled not with joy but with anxiety, clutching weapons in their hands against those who were poor and isolated.

Over the radiator of the vehicle hung a golden strip of material bearing an inscription in black letters: "Honour the leader of the Germans - the wise, courageous and great Adolf! Eternal glory to Hitler!" On either side of the inscription lay signs of the swastika, like the tracks of insect feet.

"O splendid nineteenth century, you were wrong!" Lichtenberg said into the dust of the air - and suddenly his thought stopped, transformed into a physical force. He lifted his heavy stick and hit the vehicle in the chest - in the radiator - smashing its honeycombs.

[from Platonov's "Rubbish Wind", 1934. Gorky wrote of this story: "You write strongly and vividly, but this, in the given instance, only underlines the unreality of the story's content, a content which borders on black delirium. I think it is improbable that your story can be printed anywhere." What happens later in the story, shortly after this attempted sabotage, bears this black delirium out to the point that it stops being fantastic. Full-body infections and fur-sprouting devolution after mutilation at the hands of Fascists, through open sores and the hot sleepy decay and nutrition of the rubbish heap, to Nazi work camps and eating the rat that has drank your blood, to a woman rocking her necrotic babies for a week past their death, to cooking your own thigh flesh to be consumed by an unknown policeman, to the flatline point of the "empty settlement, where the life of human beings had been lived to the end, with nothing left over."]

Spirit is a bone and this is a drill

What thought is as if, if thought is as though a bone drill.

[clip from Frankenstein Must Be Destroyed]

That flame got me

A video in which bands march and cars burn. The revelation of pull-back tracking shots, so that we're dragged ass backwards through what will come to surround the object of attention, and a reminder that we only see the flames when we're already past them. (That, and J. Cole proves that he pretty much deserves to be the next big thing, or at least that BBGUN needs to keep making videos.)

A perfunctory filling-in of peep-show time

"Character and story have faded into the background, suspense and surprise simply do not exist, plot has become a perfunctory filling-in of time between each macabre set-piece. The logical development of this kind of thing is a peep show of freaks, interspersed with visits to a torture chamber. It is a depressing and degrading thought for anyone who loves the cinema."

1956 Tribune review of The Curse of Frankenstein

The unquiet earth, 2 (on post-catastrophic realism, inhuman human nature, naked boys with nosebleeds trying to set themselves on fire)

[excerpt of last chapter of Combined and Uneven Apocalypse, following from yesterday's post]

What, though, of another common articulation of “persisting through the dead world,” not producing the urge to pull the plug on it all but rather the struggle to survive after the fact? We speak here of films that are neither apocalyptic (the event and its revelations are happening) nor post-apocalyptic (the attempt to move forward or build otherwise in accordance with what has been revealed.) Rather, they are post-catastrophic. Something has caused the collapse of society, and we are asked to focus on the quiet desperation and explosions of savagery in the contentious attempts to preserve structures and memories of pre-Event normalcy. This has echoes in films and genres considered earlier but finds its dourest articulation in the dystopian realism of the post-catastrophe model, films such as End of August at the Hotel Ozone, Time of the Wolf (2002), The World, The Flesh and the Devil, Blindness (2008), and, The Road (2009).

These are often very serious films, equally serious about being high art; with that comes both a certain portentous gravity and the capacity for innovative misanthropy. They also share a very marked resistance to explain exactly what sort of catastrophe happened, or at least what triggered it. Therein lies their catastrophic nature: the previous order (and way of ordering human society) has come to a definitive end, but nothing was revealed, no glimpses of totality or of what has been structurally excluded from that totality.

At most, we see two things. First, we see the material after-effects of that catastrophe: stillness of the blighted landscape, undrinkability of its water, and various consequences of long-time pollution or nuclear winter. Second, the rapid degeneration of the social contract and the emerging degeneracy of people finally let loose in a post-state system to be as bad as they’ve always wanted to be (or that they “cannot help” being). Insofar as these two tendencies are related, the lovely melancholy of the ruins and the visions of pseudo-scarcity function primarily as a backdrop to the all the bad things people do to one another and to other living things (cannibalism, rape, torture, ritual sacrifice, kicking out strangers because you can’t trust anyone).

And crucially, this isn’t the sort of violence enacted by an emergent dystopian authoritarian order: not systemic exploitation, nothing of the sort of emergent iron fist of Orwell, Judge Dredd, or Aeon Flux, not even neo-nomadic marauders with the prospect of forming a group to be reckoned with. Rather, sloppy assemblages of the scared and hungry, abortive communities, and hollow remnants of nuclear families. The rhythm and texture of these films is analogously marked by this disconnect between setting and behavior, with glacial pacing and tableau framing, out of which the barely repressed explodes again and again: a quiet earth, perhaps, but one on which noise and fury are the rule.

At most, we see two things. First, we see the material after-effects of that catastrophe: stillness of the blighted landscape, undrinkability of its water, and various consequences of long-time pollution or nuclear winter. Second, the rapid degeneration of the social contract and the emerging degeneracy of people finally let loose in a post-state system to be as bad as they’ve always wanted to be (or that they “cannot help” being). Insofar as these two tendencies are related, the lovely melancholy of the ruins and the visions of pseudo-scarcity function primarily as a backdrop to the all the bad things people do to one another and to other living things (cannibalism, rape, torture, ritual sacrifice, kicking out strangers because you can’t trust anyone).

And crucially, this isn’t the sort of violence enacted by an emergent dystopian authoritarian order: not systemic exploitation, nothing of the sort of emergent iron fist of Orwell, Judge Dredd, or Aeon Flux, not even neo-nomadic marauders with the prospect of forming a group to be reckoned with. Rather, sloppy assemblages of the scared and hungry, abortive communities, and hollow remnants of nuclear families. The rhythm and texture of these films is analogously marked by this disconnect between setting and behavior, with glacial pacing and tableau framing, out of which the barely repressed explodes again and again: a quiet earth, perhaps, but one on which noise and fury are the rule.

Underpinning this all is a deep commitment to a certain conception of the human animal. At the end of history (here defined as the narrative of a civilizing project tending toward the global stalemate of liberal capitalism), we discover that our capacity to act badly is not historically contingent or determined. More than that, we see that whatever the accidents of history were, whatever the repressions and imbalances that shaped the globe, they were ultimately a necessary corrective to the chaotic fury of the human unchained. According to this perspective, one far more common than a set of serious-minded art films, it isn’t that we act badly because the reigning order’s mechanisms of exploitation and domination were rewarded and learned.

Nor is it that the catastrophic undercutting of those structures left a void into which the learned patterns could only continue in a bloody and relentless recurrence of the same: what else do we know how to do, other than steal, rape, cheat, and kill ...

Nor is it that the catastrophic undercutting of those structures left a void into which the learned patterns could only continue in a bloody and relentless recurrence of the same: what else do we know how to do, other than steal, rape, cheat, and kill ...

And so for all their emphasis and lingering gaze on the material traces of the catastrophe, these films cannot help but evoke a deep anti-materialism, as we are asked to treat the savage behavior we witness as the transhistorical brutish underbelly of the human animal. In other words, we are invited not to see it as the consequence of a social organization that has conditioned such behavior but as the consequence of that social organization no longer existing.

However, what of the fact that these films are in many ways “about” the preservation of older forms (the family, commodity artifacts, storytelling and history, constant appeals to what we do or don’t do)? In its most recent iteration, we might think of the insistent commodity fetishism of The Road, as if the way to preserve the best parts of the Old is to give your son the fizzy New in the form of a can of Coke. But the genre tendency remains capable of sharp critical intelligence, and it’s clearest in the way that it undercuts so much of the post-apocalyptic emphasis on remembering the Old as the necessary mode of salvation. Transhistorical brutishness may still be waiting in the wings. However, the solution may not necessarily be the frantic grasping at whatever tattered remnants remain. In fact, those solutions may do far more harm than good.

Two brief examples. In The End of August at the Hotel Ozone, Jan Schmidt’s sparklingly bleak film, a band of Czech doomsday female soldiers roam a post-nuclear world of ruined and overgrown cities, argue, and torture animals. If they are the face of the New, the New is often mute, rather feral, rather sexy, and deeply aimless: mercenaries without direction, supposed reproductive potential with no future. The preservation of the Old order is the task of two characters in the film: an old woman who leads them and an understandably bewildered old man upon whom they happen. (We might fairly sympathize with his flustered confusion at their attempts to flirt with him: the transition from last man on earth, holed up with memories, to a confrontation with this gang of proto-riot grrls, is a bit of an epistemic shock.)

The film is, at its most basic, a nihilistic and relentless destruction of the Old. Despite the attempts to inscribe personal memory as an antidote to the end of history, especially in the compelling shot in which the old woman counts back through history via the rings of a tree stump, the total disconnect between what was and what is can only blossom out into violence. There is an uncrossable rift, leaving only the sense that those unmoored from historical knowledge will be the death of us all. Or, rather, the second death of us all, after the first death of the nuclear winter. It remains unclear, however, just who is unmoored from history, for despite their destructive urge and inability to recall or adhere to older structures of social collectivity, the vital intensity of the women remains the only spark of life.

The question becomes moot. Eventually, following the death of their leader, the soldiers kill the old man for his gramophone, the last vestige of culture. And what was he protecting, holding out for the potential future to come? A single 78 rpm disc of polka, “Beer Barrel Polka (Roll Out the Barrel).”

If End ventures the fundamental incompatibility of the post-catastrophic New with the teetering and musty records of the past, Michael Haneke’s Time of the Wolf pushes further to insist that it isn’t simply that our old modes may be defunct confronted with the barbarian inheritors of the vacant earth. They may directly stand in the way of reclaiming a social decency, and they threaten to destroy the potential agents of a struggling advance forward. The nuclear family is destroyed, as the father of our protagonistic group is shot a couple minutes into the film, and what emerges is an emphasis on new mythmaking, as a groundwork for understanding heroism, sacrifice, and communal good in a time of total despair. A story is told of the “35 Just,” the elite group who safeguards humanity, and of sacrifices for the common good.

But where does it lead?

To a naked boy with a nosebleed trying to set himself aflame on the railroad tracks. Saved at the last minute by a guard, the boy is told:

“You’d have done it [self-sacrifice to save the others], for sure. Believe me. You were ready to do it. That’s enough, see. You’ll see. Everything’ll work out [...] It’s enough that you were ready to do it.”

If this is a slightly more positive version of the notion of retroactive species valorization by collective suicide, the emphasis should be put on the “slightly.” Haneke’s formal distancing keeps a sense of judgment from encroaching too heavily, but it certainly should be noted that the embrace and “saving” cannot remotely compensate for the deeper horror of the logic encouraged here. I’m hard pressed to conceive of the full scope of an ethical logic in which it is remotely good that he was “ready to do it.” Aside from the functional uselessness of a suicide in a filmed world where the mystical power of self-sacrifice seems entirely lacking, this comforting gesture is the worst stain of the Old. For when everything doesn’t work out, as it likely won’t without a lot of hard work and without arbitrary suicides, it is too easy a step to think that perhaps being merely ready to do it isn’t quite enough ...

From the absence of causal links between environmental after-effects and their sources to the incapacity of remembering better to stop the directionless march toward nihilism, these films draw out the full emergence of inhuman human nature. It is a notion to be pursued through the rest of this chapter and beyond, in its dual senses. First, a historical formation that results in behavior fundamentally opposed to a humanist conception of the kind of creatures we are. Second, a longer sense of the absence of originary human nature: it has never been anything more than the deviation from what we assumed to be originary, it lies in that assumed perversion itself, that unlikeness to itself. An initial stab at this should ask:

Why do the vast majority of apocalyptic fantasies assume that things going bad will lead to human relations going far, far worse?

Why does the end of capitalist days – and the revelation of the undifferentiated – so often entail a return to a vaguely state of nature, a state that few of us know beyond these cultural visions?

To approach these questions, incompletely, we should follow the turn at the end of Time of the Wolf. After Ben’s abortive suicide, the film cuts to forest and verdant green shot from a moving train, a third party perspective with no human behind it, as if all that remains to be seen at the end of history is nature itself, seething silently and waiting its turn.

The unquiet earth, 1

[Combined and Uneven Apocalypse will be coming out sometime at the start of 2011, which gives it one year of existence before 2012 wipes us all off the face of the earth like crumbs. As such, I'll post some teaser excerpts from the final chapter - which is on post-apocalyptic cities and things like nature and bad behavior and Godard and Snake Plissken - every so often in the months before it becomes a heavy paper object. Some of this has its far earlier roots in the initial posts on apocalypticism back before this became a more all-consuming project. Some of it is far more recent.

The final chapter takes on four figures of the city:

1. The city as ruins emptied of human life, a melancholic remainder and reminder of the voluntary extinction of the species at our own hands

2. The city at war with nature, on the losing end of an ongoing battle to assert itself in the face of deep ecological time and the constant push of the green into the gray

3. The city as site of uneven time, of the coexistence of apocalyptic zones with the overall functioning of commerce and urban daily life

4. The city as time-out-of-joint zone within the world order as a whole, the consciously neglected site in which collectivities may begin to emerge

What follows is a bit on the first.]

Post-apocalyptic cities tend to cling to the far poles of a primary opposition between the empty and the full apocalypse, the barren and the teeming. They oscillate between loners wandering the evacuated sites of life and abandoned hordes swarming in some reclaimed outpost of lost humanity. To be sure, the most subtle iterations claim a space that is both (think of the plague city of loners flooded with the walking dead, at once the excess of bodies and the apparent desolation of life).

Running beneath this opposition, however, is a consistent aesthetic and affect of the city “after the fall,” namely, the melancholic contemplation of decay, the dysphoric nostalgia of reveling in what can never be the same again. It is not, however, a question of being alone in the urban mausoleum. To draw from film: there may be a single survivor who eventually finds a few others (The Quiet Earth [1981], the Matheson versions [I Am Legend/Omega Man/Last Man on Earth], The World, The Flesh, and The Devil [1959]); there may be a band of them (End of August at the Hotel Ozone [1967], pretty much half of all zombie movies ever made, the more lyrical parts of Terminator Salvation [2009]); there may be a whole city holding out against the wilds and wild things pounding at the gates (28 Weeks Later, Zardoz [1974], in an odd way). The thread running through is the fantasy of the contemplative museum of ruins, a waste zone (echoes of Tarkovsky’s Stalker and Marker’s Sans Soleil intended) that cannot be escaped: all that remains to do is to mourn without ever putting the past properly to bed. Just the pornography of decay, perhaps experienced en masse but never collectively.

In Tarkovsky’s Stalker (1979), a consummate film of the broken world’s loveliness, the sort of extra-urban Zone, guarded by the military, is a space closed off from “normal” life surrounding it, in all its decay and Soviet rust-belt prettiness. In our move away from the global event version of the apocalypse, we find again and again the borderland and the bound, the space encircled to keep without and within. Yet in Stalker, what is preserved (as the emancipatory potential of a post-apocalyptic, post-rational Zone) is the hollow, an empty anti-commons. The vestiges of day-to-day existence become otherworldly in their vacancy, fused with a halting spirituality notably absent in the far more subtle novella (the Strugatskys’ Roadside Picnic) that forms Stalker’s source. This runs the full gamut from a faded painting of Lenin’s face, watching over an abandoned room, to the sad, silent majesty of interior sand dunes that may as well be burial mounds.

Geoff Murphy’s New Zealand doomsday film The Quiet Earth (1985) has the conviction to stick with the going-insane reality of a lone survivor, scientist Zac Hobson, for a decent chunk of the movie. It tempers this with some needed pleasure, a whole lot of rage, and some unforgettable visions of how to take revenge at a world with no one left to blame (other than yourself). Notably, we see a balding man dressing in a woman’s slip and Cesar robes, pontificating from a balcony to a pre-recorded soundtrack of applause and an audience of cardboard cut-outs of luminaries such as Adolf Hitler and Bob Marley.

This is quickly followed by a consummate revenge fantasy: shotgun in a cathedral, blowing away crucifixes, and getting to declare yourself God. Unfortunately, however, the film cannot quite take full pleasure in this, or even in the more mild forms of indulgent joy in fucking with the remnants of a world suddenly without other humans. (Aside from watching our protagonist enjoy a breakfast of a raw egg cracked into a flute of expensive champagne, the great moment of sheer pleasure comes when we cut from a model train circling aimlessly to watching Zac drive a real train.) Instead, it hints from the start that there is something fundamentally wrong with making a racket. Even before Zac discovers two other survivors and develops a normal living situation tensed around a love triangle of sorts, the film already hints that his need to yell loud and destroy the edifices of that past life are wrong, that the correct relationship to the land of the dead is deadly silence and quiet contemplation. One should lead a quiet life on this quiet earth.

Folded into this is an odd assertion of the strength of resignation. The three survivors all survived the galactic disruption of the “elementary charge” because they were at the moment of death: at the respective losing ends of a fight, a faulty hairdryer, and one’s own hands, slipping into a pill overdose slumber. (There are connections between the individual decision to end one's life and the "end of the world" landscape, but here, we can imagine it turned otherwise, back onto a system-wide level: to willfully push civilization to the point of total collapse so as to therefore mediate the terms of that collapse, to weather the storm and be ready to come back from death. The worst of bellicose apocalypticism.)

The broader issue is how our melancholy, yearning, or resignation is marked spatially. We could return here to the function of the dream-image thinking its utopian future, shedding off the accrued material of the recent past and sliding back toward the impossible time “before it all went bad.” In these examples, and running throughout the genre as a common tendency, the fantasy of utopian “liberty” and the visions of an other world are located in the site of the past. And on this site, we encounter both the doomed nostalgia epitomized by strains of primitivist thought, at best, and, at worst, a form of Hegelian logic distorted beyond recognition: the strangers' encounter in the forest, to be mediated and navigated into the master-slave relation, is instead writ species wide into the fantasy of the human race confronting itself in mortal combat.

To be clearer, here, we might think of the recurrent instance in post-apocalyptic culture (for example, in Hiroki Endo’s Eden: It’s an Endless World! manga series) when an individual subject acts willfully – or hints at the desire to do so – in order to bring about the death of the species as a whole. This is neither bald misanthropy nor the kind of anti-human logic espoused by certain radical ecological movements (though the manga series does articulate plenty of those “the earth would be better off us and our attendant damage” sentiments). Rather, buried within all their survivor-guilt and loathing of “what we’ve become” is the dangerous gambit of a properly apocalyptic dialectical ethics.

The human race is only worth preserving if we have the courage to make the willful decision to exterminate it.

More than just the petty “scorch the earth and reset the clock” fantasy of posturing black metal bands, this is the paradox suffocating and structuring those who face the bloodbath of the 20th century as well as those loners wandering those waste zones on the other side of the irreversible catastrophic event. Like the being that must be unlike itself to prove that it’s more than bare drive and instinct, the impossible thought here is that only suicide proves that you are indeed an autonomous subject.

Species-wide Russian roulette: you have to pull the trigger to realize that you never should have done so.

South Riding 2: An Immodest Concrete Proposal

"Winifred Holtby realised that Local Government is not a dry affair of meetings and memoranda:- but 'the front-line defence thrown up by humanity against its common enemies of sickness, poverty and ignorance.' She built her story around six people working for a typical County Council:- Beneath the lives of the public servants runs the thread of their personal drama. Our story tells how a public life affects the private life; and how a man's personal sufferings make him what he is in public."

If there is a film more made for Owen, I haven't seen it. From '38, a melodrama focused on the thrilling world of a South Riding town council as they fight over the location of a new council housing project to replace the shacks of the poor they will demolish. (The film has the odd sense of reversal: it isn't that it skimps on the meetings to focus on sex, romance, and action. Oh no. There is a lot of hot and heavy debating action and insight into the white-knuckle world of zoning decisions.) Features a trenchcoated consumptive Socialist who coughs every time he makes a political point. It's a film which implies that Brits may really want socialist policy, but they would really prefer them to come from the landed gentry, who manage to successfully dismantle that identity at the very moment of a) getting a bit ethical, b) sealing the deal with the ex-feminist school teacher with whom you've birthed a calf in the most hypersexualized bit of shadow play I've seen since Robin Hood: Men in Tights a long, long time ago, and c) successfully screwing over the local bourgeoisie in a fantasmatic alliance between People Who Work the Earth and People Who Own the Earth That is Work. Also, there are a number of drawn-out school girl fights.

And yes, as my friend Hunter caught, there is an perhaps unintended, prophetic pun suggesting a "concrete proposal" for the planned Council Estate.

To top it all off, given that the squire's failing estate is donated (i.e. sold for cost of mortgage) to the project, thereby foiling the dastardly schemes of the town's small business owners and hucksters, on the one condition that the manor itself be preserved and used to house the high school run by said squire's schoolteacher/class traitor/woman who gets the soft glow treatment, the film basically ends with the unspoken prospect that what the town will now have is, basically, Bevin Court encircling a 15th century country house. Stranded somewhere between a dream of insane repurposing (schoolgirls learn about the death of the aristocracy amongst their lost halls and scribble graffiti in their marble bathrooms) and the wet thud of socialist planning coming to rescue of the embarassed, outmoded landed class trying to save face.

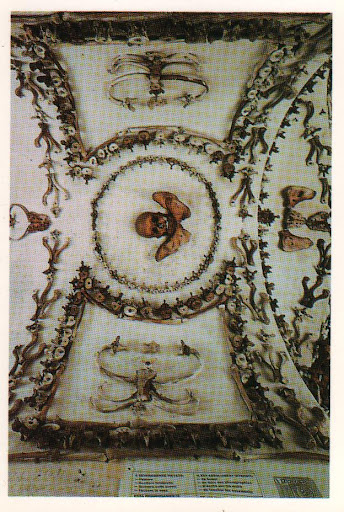

Roman letter 17 (on decorative arches made of pelvic bones and the imbecility of existence)

R,

A wall is covered with a thousand ilia. They are creeping, nestled wings and they do not ripple in the wind and there is no wind.

Other than the joining exhalation of mango-flavored lip gloss and centuries of musty rot, that is.

I'm in the Capuchin Crypt, near Piazza Barberi, where you go up two flights of stairs and down three, and the complete skeletal systems of four thousand friars are stuck to the walls, ceilings, arches, femurs stacked like thin cordwood, careless worn skulls, polished by 30 years in the dirt before dug back up and pulled off the body.

And a single skull is tacked in flight, on scapula wings, to the ceiling.

Below it there crowds one of the worst gatherings the human species is capable of: forty-three German pre-teen tourists, teetering on the earlier edge of puberty. They reek of shampoo and decades of mediocrity to come, and all of them are wearing matching red scarves knotted around their necks so they can be identified when they wander off down darker corridors to try to make out and fumble the hinges off an unnecessary bra. They are pink-cheeked and bleach-tipped and the little shit next to me absolutely will not take off his sunglasses.

They are filing past an arch of pelvises, stripped of dicks and flesh, like dinosaur heads but without tendons and testicles.

Bone flowers everywhere, repeating loops and sprays of hard yellow calcium. Jumbled bodies, a mass grave made into wallpaper and folly. A Todesspiel.

On the wall is written:

Il mondo come noi lo conosciamo sta passando

The world as we know it is passing

The crucial point is that it's passing, not past: this isn't the friars' lament from beyond the grave in which they don't rest. This is the bones talking, the same thing they say when surrounded by a body that lives as when surrounded by a nailed cluster of other ribs that have no corpses. The knowing of world, as bones know it, is a passage, an order and arrangement, a set of structural distances and negative space against gravity Whether that means the supportable weight of a span between metatarsals or the correct distance those same bones to spell out a rhythm that doesn't move and sits to remind sweaty adolescents that their ripe loins too will rot.

The crypt protects against such thinking and then it goes on to dismantle its own protection.

For there is a concession to guard some principle of the unified body's coherence, as if a body – rather than the scattered bits and pieces of some bodies – was still the ruling measure here amongst these flurries without meat. Hence the insistence on keeping the few full skeletons, with their dusty brown robes and hoods draping low over the teeth that don't have gums and this is supposed to ward off the fact of everything else, of coming undone into the more monstrous particulars, or it can bolster the stated pedagogical function – to remind us of our transience, hence we should get good with God because all our vanity will come to naught, or at be relegated to one slightly more attractive ulna than the rest of hundreds fanning out – by providing a midpoint in the dissembling. Ruddy cheeked biscuit-fed tourists carrying guidebooks : hunched skeletal friars : five-hundred and eighty-one foramen obturators dotting the wall like snow.

Or there are figures we know: an hourglass, a scythe, and yes, they are formed from things that are not glass and metal. That curving blade is a cobbled together set of scapule, and we turn to those in front of us, start taking them apart in our sight, envisioning his skull a goblet, her leg a cane, not to be whittled and fashioned but all along, these things as finding their form only after the death of the one who carries them. The bones lose origin, because when you crook your head, yes, there is something clock-like there in you, and now you are not a man, you are just a rather chubby cargo shorts-wearing clock waiting to be stripped down.

But all this still implies design for: the full body designed to carry upright, the proper fit of bone to approximate a known figure or to be gripped by another hand. A reaper who needs no scythe, just puts shoulder to ground, wheat, neck.

But then, but then there's the fact that the body contains 206 bones.

And where the crypt starts to come apart, where it undoes the centrality of the body as ordering device, as thing to be held or lost, is this principle of completion, that when a body falls down and the skin peels away, you aren't left with just a skull to hold and polish, or a couple femurs to cross below it.

And there are 4,000 dead friars. And 824,000 bones.

What to do with 4,000 scaphoid bones, which are not allegories or signs? We cannot look from them to our wrist and think, oh yes, that belonged to someone as this little piece does to me, and oh, mortality, you cruel master. I stood and looked over these bones and I did not know where they belonged, if they helped hands turn pages or asses hang over holes or teeth crack through other little bones.

The need to use every bit renders the bits inhuman.

At most they become animals, fossil echoes.

The sacrum is a hollow turtle and they are everywhere.

Lower jaws are paired with each other, which means they are transformed into shark jaws, with the teeth facing wrongly.

Bent wings of clavicles swooping low.

Though these are the exceptions, the searching eye finding something that sticks, like looking toward clouds.

Above all, it does not work, and the dissembled bones are just ornament, faced with total non-figuration and non-recognition. We ask only what the hell is this bone, we have to reach it with the double knowledge that it belonged to a body and that it cannot be known as such for it is simply an architectural detail.

Even when the three full friars are propped up in front of us, like a weak haunted house, where their grimacing skulls are supposed to draw the eye, sight wanders and they are standing below arches of vertabrae, from other countless bodies and there is nothing horrible in the full clothed skinny men, only perhaps in the fact that they come to mean so absolutely nothing beneath and between this frenzy of figureless detail.

Walls of dots of padellas, wavering polka dots.

The hooked socket of the ischeum.

The different speeds of the vertebrae, a pacing, halting wave alternating thoracic and cocygeal.

A blunt chipped tarsal period.

Vile hooks of rib broken from the cage.

In the furthest room, the one set sequentially as last, there's a small sign posted at the center. It reads:

QUELLE CHE VOI SIETE

NOI ERAVAMO;

QUELLO CHE NOI SIAMO

VOI SARETE

What you are

We were;

What we are

You will be

Next to me, this dismal tourist couple – dressed, because they are American, in clothing far too technical and ready for long-term desert trekking than is necessary for wandering from church to cafe in Rome, but that's what Americans do, because they like to imagine all of their trips as excursions – snuggle and he says, that's a good reminder, isn't it honey? and they have a reassuring kiss and they actually will remember this moment and say, you know, it really put things into perspective, you just have to appreciate what you have before it's gone, while we can still be what we are, not were, still wear sandals and spoon each other in the night with the AC blasting cold so we feel like we need the warmth of another body.

Chatelain wrote of this place:

and what appears to me yet more disgusting is that these remains of the dead are only exposed in this manner for the sake of levying a tax on the imbecility of the living

He's right on one count, wrong on two: the imbecility of the living is in full gawking bloom, texting their friends while feeling sweat dry on their clammy knee-backs and hoping to cop a feel. But it's basically free these days and what taxes, if not money, isn't the other side, the supposed confrontation between the living and the dead.

A confrontation that cannot occur, as the forces are so dissimilar as to stare dumbly past each other. How does a German tween in a apple-green polo shirt look at a skeletal baby stuck to the ceiling that is not the bones of a baby, but a borrowing of the smaller bones of an adult, so that a rib is not a rib, but something small and ribbish enough?

And this is what horror gets wrong, or at least the way we tend to talk about the horror of sights like these, which wants to imagine the node of the horror effect as the consequence of a speculative leap, of being complete and constant, and aware of that fact, past the point of life. I know now that I will be a skeleton, I will be dry and empty, and what's so bad is that the little word – I – sticks straight through. That's the flat awfulness the clutching couple thought they spoke of.

But that's not it, of course. It's the wrong use that's worse. It has nothing to do with death. Only with misplacement, or worse still, perfect placement.

Not that you'll be dead, not that you'll be forgotten, but that you'll be employed, un-wholely, in a design beyond you, that cares not a whit for some I that was planning to persist and now finds itself parceled out into 206 potential serifs, rays, arcs, sprays, points, and curls.

And what is this if not the basic fact of economy itself, in which we are waste to be managed, in which even the unimportant bits get squeezed and turned, made into value? By value, we mean: that claims its worth on the ground of that dismantled I yet which is utterly hostile to it. Which doesn't build the forms from scratch or wait for something to decompose into usable chunks but which eyes hungry what is already the other thing it could be: engine, clock, hour, tendon, axe, sweep, delay, glue.

And it hisses, like dry steam, the missing line

What you are now, we are now

That is, a collection of objects, teetering on failure, the woodpile gnawed from the inside out.

An organization dreamt of as utilitarian, all things built for their purpose, but so too these lesser bones, which join and hook together to soar low, these bones that do not belong to anything more than this.

We are already these things, not just because we're dying from the start, not because we're a war against rot, which we may well be, but more because the bones urge to be useless, to be ornament, and they urge toward something else, something more vicious that we call value and that means nothing other than that whirring tangle of scalpel and glue, which itself founds a urge to find that place for them, in the tired sweep toward making more of this world, of making sure that what we are now is what we will be and have been then.

Anyone who talks of totality must talk ultimately of this. The recognition that it is no longer about the single clavicle that matters and that maybe we break or someone digs clutching at when fucking or over which a necklace might rise and drop, but only the horde of them all, coming and fixing together in arching curves. They write in cursive and say no thing.

Yours

E

'My dead lady, where is the State which guaranteed those securities to you? It is dead.'

In the large banking hall a great deal of business was being done... All around me animated discussions were in progress concerning the stamping of currency, the issue of new notes, the purchase of foreign money and so on. There were always some who knew exactly what was now the best thing to do! I went to see the bank official who always advised me. 'Well,wasn't I right?' he said. 'If you had bought Swiss francs when I suggest, you would not now have lost three-fourths of your fortune.' 'Lost!' I exclaimed in horror. 'Why, don't you think the krone will recover again?' 'Recover!' he said with a laugh... 'Just test the promise made on this ao-kronene note and try to get, say, 20 silver kronen in exchange.' 'Yes, but mine are government securities: Surely there can't be anything safer than that?' 'My dead lady, where is the State which guaranteed those securities to you? It is dead.'

...

the large numbers of unemployed, their passions fermented by the Communists, are seething with discontent... a mob has attempted to set the Parliament building on fire. Mounted policemen were torn from their horses, which were slaughtered in the Ringstrasse and the warm bleeding flesh dragged away by the crowd... the rioters clamoured for bread and work... Side by side with unprecedented want among the bulk of the population, there is a striking display of luxury among those who are benefiting from the inflation. New nightclubs are being opened. These clubs have the effect of greatly intensifying the class hatred of the proletariate against the bourgeoisie.

excerpts from Anna Eisenmerger's diary, in Adam Fergusson's When Money Dies: The Nightmare of the Weimar Hyper-Inflation, a book which, perversely, both Warren Buffet and I recommend, albeit for drastically different reasons

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

.jpg)