This, of course, after it had lived for 24 years impaled on a spike above Westminister Abbey. After it had been separated from his body, which had already been dead, which had been dug up to reopen old wounds, to be dragged through the streets and hanged.

The multiple executions of one already expired. Such is the State's really good comeback line thought of the next day.

Insurrection for a prom night

John Maus - Cop Killer from Know Phase on Vimeo.

Riot porn has found its soundtrack of the times, a stateless coup d'état dreamed up drunk in the backseat of a car. Yet this is no adolescent fantasy of the few. More the scent coming through the open window, something much larger, slow, something magisterially ugly.

With all the formal driftiness of grainy footage. With the grandeur and delay of pixels that can't quite register the speed with which a scatter of gasoline takes off, along the tar, up the body, across the shields, already fire before it gets there or got itself lit.

Baby, don't move. Don't move a muscle. The landscape has come in through the window. I don't know how. It is an ideology of nature or something, off its rocker. I don't know. But it falls on us like a monolith, like a guillotine, like a pastel, like...

You're beautiful like this, you know that, don't you?

Applied Nonexistence

Check and track and know: promising (in the sense of that which aims to break tacit promises, including its own) project from Oakland environs, Applied Nonexistence. It is, after all, "for the refined connoisseur of anti-political negation theory." Judging from proposed projects getting off the ground, it's laying a few negative lines to follow out. And insofar as such lines deserve the designation negative, we'll take as many as we can get.

After all,

For every tumor, a scalpel and a compress.

For every scalpel, a scalpel.

Oh my goodness

Not drums as chronometer to set a pace over which to talk about guns and how they might sound. Drums as - and is and are - guns. In a sometimes hurry, like martial order breaking into a scared run. They sputter.

Voices learn - or do not, at their own peril - to catch up. They stutter.

I'm not going forward...

Salvagepunk In The Birthgrave

One week from now, in London. Getting busy getting done with a concept we had been busy getting off the ground.

And you will be fried in a variant of the very substance that you are, separated by a thin armor, and you will be consumed by that which is you are, rendered almost mobile and often capable of speech. And the money exchanged, rest assured, will bear your traces.

Forget the whole "sugar without sugar", "coffee without caffeine." We speak of a substance wrapped, soaked, and crisped in itself.

O homeland! You are far from me now, they have taken our line of sight from us, they have erected oceans, and I have aided them in doing so.

But still, still I can smell you, oil thick in the lungs of us all.

The dogs, sniffing, tracking the sodden earth, sudden lost the trail. They turned in circles, doubled back on their paths. And she knew then, the thought dawning slow, exactly had happened. The scent they had been tracking all along had been nothing more than their very breath.

O homeland! You are far from me now, they have taken our line of sight from us, they have erected oceans, and I have aided them in doing so.

But still, still I can smell you, oil thick in the lungs of us all.

The dogs, sniffing, tracking the sodden earth, sudden lost the trail. They turned in circles, doubled back on their paths. And she knew then, the thought dawning slow, exactly had happened. The scent they had been tracking all along had been nothing more than their very breath.

Other than all that (Notes on Transformers 3)

[It's rare to watch a film that produces a portrait so faithful to how it is to watch it.]

1. I have never sat through such a long porn film. Or one with so little plot.

2. It is oddly beautiful at moments. A massive honeycomb grid planet, a Bucky Ball writ cosmic scale, almost touching the earth before collapsing in on itself with a soft implosion of rust and creeping fire. But the rest of the time, it feigns beauty by simply making the eyes hurt. But not the cognitive faculties: it leaves them dull and barely frayed. For to wound those would be sublime, which this is not.

3. There is no point in an ideology critique in the face of such a film, because it doesn't have an ideology. It has a howling wind, dreamt up in the belly of a CGI rendering program, that lifts and carries things, that makes other things pass in front of our behind them.

Among those things are the bad robots. They are coded as either Arabic (wearing scarves, despite the fact that no other robots wear clothing, camped in the same desert environment where we see the good robots kill bad - or at least wearing aviators, sweating, and with a severe expression - brown people), black (literally black paint, long flowing robot dreadlocks), cops (now we're getting somewhere!), murderous birds, giant Dune-like burrowing worm-snakes that burrow through and python-strangle skyscrapers, and trolls.

The good robots are coded as, alternately, assholes or the vehicles driven by assholes.

4. Total, utter absence of desire, on all parts. There is a young woman of sorts, who is supposed to be incredibly hot, or so the film goes to great lengths to point out, from an opening gambit of an ass-level tracking shot up the stairs, from nearly every character, to a degree that starts to erode its own belief in this fact. But she is a pure cipher: can we all agree that this set of parts constitutes an approximation of an ideal of the kind of woman audience members want to stare at in 3-D? No, not her in her particularity, but as an aggregation, as a technology, as likely at any moment as any car or truck to suddenly dissemble before our eyes, and reform into something that also does not especially resemble a human but can be expected to pass for one provided that the camera move away too quickly or linger too long, such that there is a false consonance between our gaping and hers. OK, then, all on the same page?

[The absence of desire is aided and abetted by the absence of any real absence, other than things like modulated dialogue. Not a thing lacks. And where it might, fluttering papers, glints from a missing sun.]

5. Many "people" "die." But not particularly. Rather, they run around a set on which some real fake rubble is strewn and, at some point, they are told to throw their arms out or fall down, at which point are erased from the film by a computer, and replaced by a quick, acceptable-for-PG-13 spray of something vaguely blood color, with a sudden visibility of a very polished skull and a femur or two. They are, that is, vaporized. Or the "camera" cuts away, such that they are probably crushed under big feet or lacerated by the spinning razors of a metal snake's tail. But there is no gore. They are not torn to shreds. They are whole, and small, boring and mediocre, and then they simply are not there. Even the man thrown through a window to fake a suicide: we do not see the impact, we do not see him open onto the ground.

6. Conversely, it is one of the goriest films of late, provided we properly anthropomorphize the robots as we are supposed to. (Or see them as lesser categories of humans, as in the racialized, exoticized, and demonized bad ones.) There is no anthrorpos violence, but there is a staggering display of violence enacted on the forms - for they have no matter or weight, just shifting colors and textures - of that which is formed [morph] as if anthropos. They dig their hand-shaped extensions deep into something we are meant to think as a chest cavity, they leak red paint and oil and anti-freeze, large chunks of rust and chunky geared organs splatter the broken city, they wrap chains around their heads and pull hard, until they come free, sputtering cables leaving it unsevered. And like the bodies of Dante's thieves, they are never all the way one thing or another: falling through the air, they are folding in and out, like seraphim with many wings and unexplainable differences in national accents.

7. That violence is utterly without any pathos or sentiment. This is due less to the very terrible story and absence of character development, which, contrary to a well-trod path of thought, is not a prerequisite for a stomach to fall and turn. It is without consequence because it is without coherence: it is incredibly difficult to see just what is happening, which robot wrist is sawing through which. This is the consequence of a terrible, terrible brightness and clutter, in which sheets of office paper rain down side by side with trails of smoke and glass that was never broken. We simply shut off, the far limit case of our own visual processing power, which, it turns out, is far lower than that capable of being registered in HD. And so it spins and hurls, spits in our faces, but our sight is a glass wall. It is porous only to a point, until the eyes are filled with light and incapable of mustering a care in the world. Particularly when that care is for the well-being of a robot that is also a truck, which is also a defense of American interventionism and the indissociable link between defense of the human and defense of the west, which is also none of these things whatsoever, just an algorithm, whirling in the midnight sun.

8. Because, of course, this is a film that lays more waste to content represented on the screen, in its richly-grained detail and yet which, in the process of its production, destroyed almost nothing in reality. Laid no waste to cities, sent rockets into no shopping malls.

Consumed nothing, that is, other than literal tons of coal required to power the CGI data processing, other than rare earths frying out from overload, other than little salmon, truffle oil, and pomegranate reduction mini-tarts for the cast, other than an extra permanently brain damaged from a rare piece of real metal, other than nerve endings and synaptic pathways burnt out, other than time itself, other than this time, writing these words, on something that is both as telling of our time as can be and as utterly indifferent to it, other than massive sums of money dematerialized and sunk into the faint shimmer of dust rising from the shuddering body of a robot rendered from scratch, other than all those hands and eyes through which these circuits pass, like that burrowing, winding worm, but without awe, without a speck of glint and worth and glimmer.

Other than all that.

Oh honey, look! It's standing up on two legs! Aw, it's trying to short circuit its electric fence...

How cute, they say? As Rilke should have said, cute is nothing but the warding off of terror.

Cute is the lustrous sheen painted over the dimmer, and flawless reflective, surface that is the uncanny. (Valley, my ass: the uncanny is a vertical mountain, miles high, of polished obsidian, perfectly smooth, but for something, a certain crack, a bend that can be seen but not felt with the hands.

I think I just saw something move inside there.

Tom, it's solid, it's just a pile of rock, what could inside?

I don't know... but it looked like a... pistons moving. Like, like this thing is a machine...)

Cute is the barbed wire fence we erect to prevent ourselves from straying onto enemy lines, into trenches and hands.

Oh look, it's pretending to be something it isn't! Oh, how simultaneously like us, crafty Odysseusians we are, and unlike us, because we are authentic!

Oh, look, it is putting its ears back and hackles up! It must be really mad! I love how fluffy they get like that!

Oh baby, the penguins understand monogamy! And devotion and sacrifice! (And how terrifyingly Beckettian, trundling 62 miles in the blind idiocy of a reproduction scheme that cannot adapt or relocate!)

Because cuteness is our age's first, and most skilled, act of camouflage. Because it does not enacted by the cute thing in question - that would be to truly anthropomorphize. It is a minimal display of characteristics that insist on a projection, an analysis, a designation by those who point and say: cute. It is the declaration that all things in the world, from bears to cars, are species traitors, forgoing their adherence and accordance to a metrics and purpose proper to themselves.

And in so doing, it misses - always - the actual camouflage that is happening, the research, the readying of haunches and teeth. Which is indifferent to cuteness, but which, rather than facing up to, rather than staring into that black wall, we focus on how big and moist are its eyes, how it would look to put a little sailor's uniform on it with a tiny cap through which the ears can pole out, how it approximates - although exactly wrong, wrong as a knife with no handle - something that looks like morality, like fidelity, like prudence, like care.

And indeed, camoufleurs are, and always will be, those who know how to care the most. Who know how to read body language. Who really know how to listen.

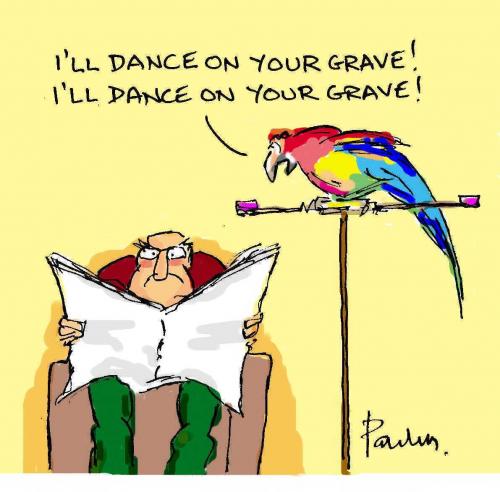

Oh my god, the parrot can perfectly imitate your voice! That's adorable! He really sounds just like you!

Three days later, John was in handcuffs, at the downtown precinct. His eyes were blank and dry. A car had run over his wife as she left work the day before, throwing her like a bundle of sticks to the ground, killing her instantly. The driver was apprehended, but after extensive questioning and accessing his voicemail, there it was: John's voice, clear as could be, putting a hit out on his wife. He denied it again and again, weeping and furious, but even he couldn't deny that yes, it really sounded just like him.

Escape From Venice, Part Two

[Part One here]

They started by sinking all craft capable of leaving the island.

They started by sinking all craft capable of leaving the island.

Elite forces in scuba gear swam the night water, around the island and through its canals, with welders and auto-muffling explosives, and boat after boat went down, gurgling and burping delicately. The few tourists awake and sober enough to catch sight of the slippery shapes moving between the wrecked hulls were promptly dispatched. However, the gondolas were left untouched, a mark perhaps of a gesture of decency that those stuck there be able to circulate their pen with relative ease, perhaps of a certain perversion that relished the thought of them fumbling themselves through the city, capsizing and cursing, without skilled pilots in costumes. The vaporettos, the large water buses that moved around and between the islands, were sunk off the south coast of Giudecca. While excessive, this was a necessary measure: no chance could be left that an Italian, out of greed or compassion, would attempt a rescue of the prisoners.

Migrant workers were massacred without notice, their makeshift rafts torched. More than one visitor, unable to sleep in the stifled air and looking out their flung-wide hotel windows, mistook the guttering flames as sign of a local holiday.

Although the truly rich had tended to forgo Venice in its drift toward total tourist saturation, the fact that the penalization of the city occurred on the last night of the Biennale meant that the gaucher varieties of the noveau riche were still there to buy contemporary art by the yard, pound, and hour, and their personal cruise ships, named things like SLAVIC DAWN and SHAHNAZ, were still anchored off San Marco. They were boarded, inhabitants taken down with silenced shotguns, and laden with incendiary devices on timers: they blew sky high around dawn, in a carefully paced percussion echoing over the city, like the tolling of bells. The rain of Gucci-logoed upholstery, body parts, and hissing champagne was the first opaque announcement to the population of what had transpired in the night.

While the boats were being scuttled, workers went down in the defunct sewers and welded new grates, installed laser sensors linked to cyanide gas jets. Floating smart mines were placed in the surrounding waters, and thermal-sensing turret guns were mounted at strategic points on the surrounding islands. San Michele, the already fortified cemetery island, became a barracks and armory, with a fleet of black Jet-Skis at the ready to hunt down any who managed, against many odds, to navigate the waters without detection. They launched predator drones, which started to circle gracefully on updrafts, as polished vultures.

Of course, many of the relatively poorer tourists had been staying on those surrounding islands. Following a long debate about two possible options (drugging them in their sleep and dumping them on the main island or strongly encouraging them that their vacations were over and that they should be glad that they couldn't afford the pricier hotels along the Grand Canal), a third, simpler option was chosen. They simply shot them in the night. A similar debate was held regarding the few Italians unlucky enough to still live and work in Venice. The hard decision was made to leave them were they were, a difficult but unfortunately necessary cost of the operation.

And so, in the course of less than 6 hours, Venice was transformed from the most popular destination city in Europe to a guardless Alcatraz. Just a generalized life sentence passed on 83,721 tourists, on those still asleep, crammed into luxury economy suites, those planning the sights to be seen the next day, those trying to get laid, those looking over photos taken an hour before, those tossing fitfully, those dreaming of strange glaciers of frozen squid ink and shameful, back-canal encounters with no less than five gondoliers at once.

At 8 in the morning, Furbino made his announcement, to the island and to the world.

Citizens of the world and prisoners of Venice,

I address you on a joyous occasion: the proud renewal of an Italy who has found her teeth once more. And in case you haven't realized, they are sharp and strong. They are the same teeth that gnawed away the fetid umbilical cord of currency that tied us to Europe.

That day, a year and a half ago, I announced a shot across the bow of Europe. A wiser breed than you all would have taken it very seriously. For we were not bellicose, were we? It was the shot of a proud and radiant beast, locked in a cage too small for its frame, a beast who had learned to use the tools of those who thought themselves its master, who held in its grand paws a weapon it knew how to use: this was the fire arm of law and finance, of will and decision. It was not a salvo to declare war: only to declare secession and warning, to tell you to keep you pasty hands away from the bars. To leave us out of your charnal games.

But you didn't, did you? You shoved your thick fingers through, you acted like you owned the place and us with it. You came by the thousands, eating our food, staining our soil, making little pouty faces for your camera phones in front of our monuments to our heritage, pissing, like sweaty, drunken boars, on the sides of our churches. You thought that you were doing us a favor by shoving your reeking money into any hole that would take it.

Well, we will not take it. And so today we offer a second shot, this time across the bow of humanity. Across the very rights you have assumed come with belonging to a nation, of having a passport, as if those allowed you to go where you wanted and do as you pleased.

As of this moment, therefore, Venice is a penal colony. We will not fill it with those who commit crimes elsewhere, but with those whose crimes took place there, on its soil and water, with those who didn't have the decency to acknowledge their crimes, calling them merely “vacations.”

Their punishment is a life sentence. They will not get the pleasure of the authentic Italian experience they so desired: we will give up none of our own to tend them, feed them, clean their filth, discipline them. You have evacuated this city of its past and its present. Very well. Let you therefore become its future. Let us see how you handle yourselves, amongst each other, with no home to which you may return. We have heard many of you saying how you “would kill to live in Venice.” I suspect you will find yourselves testing the truth of those words sooner than you think.

But we are not the barbarians here. That would be you, with your humdrum polyglot babble. And so we will not let you starve. Besides, you paid good money for your time in Venice. Therefore, crates with enough food to live on will be delivered to the docks. How you divide it up is for you to figure out.

As for you affronted nations, you loved ones back home, you shocked and appalled: are you truly surprised, or do you merely think yourselves obligated to act as such? In this day and age, what are a few lost to the damp winds of history? A few who had it coming, a few who should be proud – and will have many years to learn to be so, or to perish – to be the base material with which a nation proves that it matters, that it alone is the form capable of making sense, of erecting a proud lighthouse, in of the disastrous, darkening storm that is our age.

And for those who don't get it: don't worry, you will. Because you know that this isn't worth a war. Because you know that at the first sign of such a move, we will slaughter them all, and all your mobilizations will be for naught. Because you know, in your sluggish heart of hearts, that you will happily throw to the wolves a few of your own lambs rather than have to become hawks once more. Because you know they simply aren't worth the cost. Take it as a cheap deal on a lesson well learned. And leave us be. As an added reminder of this, from this moment forth, all of Italy's borders are permanently closed. All trespassers will be shot. We will set the hounds on you.

And for those on the island who don't get it: don't worry, you will. The passage of time is a remarkable teacher. Because you know – or you will know, when you feebly try – that there is no escape. I am sure some of you will devise grand schemes. I am looking forward to seeing their torched remains brighten the night. Should you get tired of your life, as you well might, there is plenty of water deep enough to accommodate you. But why turn your back on a lifetime in La Serenissima, even if it gets a bit wild?

I'd say I'm sorry to have to break the bad news to you. But I'm not. And it is, after all, a new dawn, on a new day, after so many years of darkness. See how clear the sky with not a touch of red, see how fast the sun rises high over us all! It looks like it's going to be a real beauty.

There was a moment of silence around the globe. First, a brief peal of nervous laughter. After all, remember the fake declaration of war on Norway hackers released from Finland's State Department World in '16? And then world leaders muttered, in a chorus of many languages, oh, you little piece of shit. You miserable, monstrous, inflated little prick. For they had been apprised of the fact that this was not, unfortunately, a tasteless gag. The footage that streamed from a set of security cameras mounted on Venice, plus the immediate condemnation from other countries, quickly convinced all that this was very real indeed. A horrible shout arose, from those in front of their screens, those pouring over email and Facebook for word from those vacationing, and from those on the island themselves, who were beginning to register the lack of vaporettos, the wrecked craft littering the canals. The corpses borne by the waves, slapping up against the stone stairs, their heads open like violet and maroon flowers. The fact that they couldn't find a cafe open for a decent cup of coffee.

Still, despite the hyperventilations, the mad rushes toward other docks where perhaps a barge remained, they maintained some degree of order. This will all get sorted out. They can't leave us here. We'll just stay calm, stick together, and wait it out. Even when a Canadian man jumped into a gondola and began rowing out toward San Michele, even when a hollow-tipped sniper bullet eviscerated him not more than 20 yards out to sea, even then they decided to keep quiet.

The normal denunciations from nations and humanitarian organizations came immediately. U.S. President Newt Gingrich denounced Furbino as “a child who has stumbled onto his father's gun cabinet and who doesn't know muzzle from butt.” Others accused him of desiring to ignite a new “Mediterranean powder keg,” albeit a century later and 300 odd miles to the west of their point of reference. The Red Cross demanded immediate access to the island. They were told “their time would be better spent elsewhere, where hope remained.” World leaders gathered quickly in Geneva to draft a resolution. Global news outlets speculated on its content, but it was generally assumed that it would involve full economic blockade, swift international censure, and threat of coordinated military intervention if the prisoners were not immediately freed.

And yet, amidst the frenzy, when they emerged from their meeting, what was presented was, to be sure, strongly worded enough (“an unprovoked war crime in a time of peace”, “unpardonable actions unthinkable from any nation considering itself a responsible part of the international order”, and other attacks relying heaving on the prefix un-). Yet it was clear to any and all that what it truly amounted to was an early admission that real action would not be taken. To be sure, they declared immediate economic sanctions and exclusion from trade, but wasn't that what Furbino himself had urged and desired for the last several years? An ultimatum was given - “You have 36 hours to immediately release those unjustly imprisoned to their loved ones and home nations” - but its careful wording excised any specific reference as to what exactly was meant by “or else you will face the full consequences of your actions.”

In short, by not explicitly declaring war, and readying for invasion the assembled nations made it clear that while they would see out the time of this ultimatum and “weigh the difficult options necessary in the face of such an unconscionable act,” they would actually follow the out given by Furbino: sever ties, leave the Italians to their own cursed devices, and take this as a relatively low loss way to avoid a larger, messier, more expensive, and, most importantly, geopolitically destabilizing war. After all, Furbino had, in a rather brilliant move, managed to align himself with a number of OPEC countries (in part by playing Italy as a victim of the ungrateful EU and their “unquestioned assertion of right to resource access”) and the Russians, whose control of westward bound natural gas had become of crucial importance in the last decade. Hence while none of these openly supported the penalization of Venice, they nevertheless crucially noted, in a joint statement that afternoon, that they were “entirely opposed to plunging Europe back into a retrograde interstate conflict.”

And so while there was a ceaseless set of deliberations, threats, sanctions, blockades, secret mission plans, and attempts to palliate the growing cries of the families of those lost to the island, it was in the night of that first day that the new Venetians knew all too well that help, if it was coming at all, was not hours away but, at the best, weeks and months off.

And it was then, abrupt as the first rock through a window, that things took a turn for the very, very nasty.

The pack, they fear, is now "killing for fun."

"It's like 'Cujo.' "

---

Webb told the AP it's possible some of the four or five dogs in the pack aren't wild and go home to their owners during the day.

Escape From Venice, Part One

[I decided that John Carpenter's Escape From New York and Escape From LA needed to become a trilogy. I decided also that serial fiction is an under-utilized form. Here, then, is a response to both those lacks.]

for Erik

In 2020, Venice had its best tourist season since 1981. This might appear surprising, given the recent state of affairs. Italy had, over the course of a decade, become increasingly volatile. In the midst of a protracted and severe global financial crisis, just after Greece finally slipped through the grasping fingers of the European Union and into open revolt, filling the world news with the rather indelible image of forty-three riot police trapped inside the Treasury by external barricades and burned alive, the fire fed by reams of worthless promissory notes, Italian Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi finally stepped down from office on April 11, 2012.

He did so, however, on the condition of two emergency resolutions. The first was an executive order for his own execution by guillotine in Rome's Piazza Venezia. This was carried out promptly, and the footage left little doubt that after the decapitation, his severed and perma-tanned head still managed to whisper one last dirty pun, as if it had been his final snickering thought as the blade dropped. The second resolution, only revealed to the public after his execution, had been long in the works. It involved the transposition of his personality and memories into an algorithm which was allowed permanent veto power on any bills drafted by Parliament. It showed itself quite willing to do so, as it brought proceedings to an extended halt, and thereby proving that the condition demanded as input by the algorithm – a warehouse full of 16 year old women in their underwear dancing 24 hours a day, their presence registered and analyzed by thermal cameras, motion sensors, and facial recognition software – be ceaselessly maintained.

In a roughly two year period that followed, from the summer of 2012 to the fall of 2014, a dispute raised by a dairy farmer turned into a 6 day general strike and threw Spain for a loop, the Eurovision contest was won by a toddler, Luxemburg was taken in a surprising coup d'etat launched by a Swiss bank, and Greece continued to intensify, as it descended into brutal civil war and was subsequently occupied by IMF-Blackwater forces. It was during this time, referred to as “The Long Pause,” that the EU disbanded, discovered new heights of currency instability, and hastily reformed, having in the meantime conveniently booted out its troublesome southern nations, with the sole exception of Italy. Despite the fact that it showed almost no prospect of a rapid economic turn-around, the political sequence following Berlusconi's mathematicization convinced Merkel and her followers that they simply couldn't do without Rome, the new anchor in the Mediterranean.

After Berlusconi got himself beheaded, a nearly unknown young politician from outside Verona named Alessandro Furbino – known earlier only from his brief spell in prison for “accidentally” killing an Algerian auto mechanic – rose with alarming speed to the top ranks of the far-right Northern League. Elected to national office, he pushed ahead a set of extraordinarily conservative, xenophobic, and isolationist measures. It turned out to be just what the EU wanted, despite the annoyance of Furbino's attempts to always put Italy first in the list of EU nations and his constant empty threats to return to a national currency, known by all to be a leap into the financial void no country would dare take.

All turned out to be very wrong, however, as he took just this step in winter 2018, announcing it during his immediately infamous “A Shot Across the Bow of Europe” speech, which promised, among other things, a “slashing of our sham ties to this odious continent of bankers and pansies,” “a new era of Italian solitude and fortitude,” and, more particularly, a rigorous new coding of regionally specific food, gaining him some accidental and utterly unwanted respect from sustainability movements and “locavores.” And in the hurried space of a few weeks, Italy reverted to the Lira, which – to the surprise of no one – fell drastically against all major world currencies.

However, due to the already imposed near-martial order, Italy managed to maintain a semblance of stability. And combined with the insistence on preserving regional specificity, a new commitment to the upkeep and polishing of monuments and historical sites (with the exception of Napoli, where trash fires, stray dogs, and, in an unconfirmed report, stray dogs who had learned how to set fires had been gaining more than the upper hand of late), the strength of foreign cash against a Lira desperately in need of some inflow, and a sense that it may not be far off before the borders would be closed to any and all visitors, an utterly perfect storm of tourism was created, one that even the increasing lack of disposable income and cheap credit couldn't dampen.

This storm hit nowhere harder than Venice, which gained a extra push from a particularly lurid and widely read report on global warming that took as its prime example the destruction of Venice beneath the rising seas and fleshed this out with a battery of expensive CGI catastrophe – The ghetto becomes a soggy grotto! – for its prime time special report. In short, one had to come to Venice while there was still something left to come to. And so they did, in droves: American, Dutch, Chinese, German, Argentinian, French, British, Finnish, Japanese, Canadian, Swiss, Thai. Even the infrastructure of a city as utterly dependent on tourist cash as it long had been couldn't handle it. The last of the residents were squeezed out of their apartments, and walls either broken down to form new luxury suites or, more frequently, added, as the combined facts of a desire for a room of one's own and the teeming quantity of those who wanted to experience Venice meant that they packed them in with a rather uncanny echo of Soviet apartments. The poorer and relatively tourist-free zones near Calle Drio ai Magazeni and Calle Sagredo, with their De Chirico minimalism of poured concrete,were transformed into hostels and multi-story gelato shops.

But even this wasn't enough: there simply weren't enough buildings to remodel or take over. “Authentic Venetian” shanty town motels crowded the squares, and new floors were hastily thrown on top of whatever houses had the load-bearing capacity to take it. (The first collapse of one such addition, ungracefully dumping sixty-one primarily German and Malaysian tourists in the midst of brunch onto a piazza six stories below, in a terrible wet crunch of bones and croissants, had almost no effect on their continued construction.) New barges were anchored to the island and stacked with shipping containers hastily retrofitted with tasteful Swedish design and tiny pictures of San Michele hung off-center in polished aluminum frames. The design for the barges was borrowed straight from the Croatian Pavilion in the 2015 Biennale, in which it appeared as a mocking exhibition of yuppie sustainability and salvage fantasies, evidently nailing its mimicry a little too well.

The non-tourist population was reduced to near zero, as waiters, police, and gondola drivers gave up their houses for reasons of turning a decent profit and, more importantly, fleeing from the further horror their city became. (This relative absence of cops provided a unique opportunity taken up by a splinter group of the recently formed Italian Insurrectionary Anarchist Federation, but their attempt to destroy what remained of the high-end retail district was foiled by a rather terrifying spontaneous mob of tourists hell bent on protecting their shopping district who, armed with tripods and water bottles, killed four of the anarchists and drove the rest from the island. The communique that followed the disastrous action was the shortest ever released by the IIAF: “Fuck that place and its visitors. They deserve one another, like a corpse deserves its vultures.”)

The workers who could afford to commute moved further and further from the island and the surrounding ones, crowding into Spinea and Jesolo, as even Murano and Sant'Erasmo become uninhabitable. Many simply gave up on working there. Those who couldn't afford a long commute – the immigrant populations to whom the new xenophobia turned a partially blind eye in recognition that they alone would take up the slack of the nasty work – slept on massive, makeshift rafts, tethered to the island like leaky balloons. The prison became a hotel – though one of the cheaper ones, to be sure. The food got cheaper and worse, although still local. The city gave up on any illusion of waste management, rerouting the sewers and dumping the trash off the sides of the island, such that it was constantly ringed with a reeking, fish-shaped halo of empty bottles, small neon objects that flashed and spun in the air when thrown high with a slingshot, tampons, unfinished squid ink risotto, and a whole lot of fecal matter.

And still they came, in their very responsible sandals and gimmick hats, their massive camera bags strapped like bandoliers over chubby middles, their common smile of those who have nothing to do in an era of decadence but “experience” and document it. They came and walked, iPads held in front of their faces, its architectural recognition software beeping and cooing when the material city aligned with the image offered by Google street view. So they walked, clattering thick into one another, jabbing slippery fingers onto the screens to capture the images, to send them to friends who, it turned out on many occasions, were unbeknownst to them on the island as well, perhaps a few steps behind. The sound of sweaty thighs rubbing against themselves sang a low and constant hush, over the shrieks, babble, and exclamations of the phrase “off the beaten path” spoken in twenty-seven different languages.

Despite all this, it still came as a real surprise to the world when unannounced, on July 8, 2020, the Italian state transformed Venice into a penal colony in the course of a single night, trapping the still-sleeping tourists as prisoners with no escape other than death.

The Black Winding-Sheet: On Labor, Meat, and Form

[this is the text of the talk I gave in Zagreb recently. Audio is available here, but given that I was having one of those days in which I speak far too quickly, it's perhaps better read than heard. Large parts of this have appeared here previously, as they were in the process of getting folded into what became this text (and a longer work in process on substance and form), which aims to draw a red thread through them and, in so doing, revisits a number of my ongoing preoccupations. The text largely sets its own ground, but it's worth framing this as part of a general attempt to develop a theory of communist pessimism.

This is perhaps similar to the arguments about hostile objects, in which the concern was to move from the seeming hyperbolic figure of a "built world of hatred and spent time" to a demonstration that such a thing is far closer to a correct capture of our world than a fantastic and overextended description of how it might feel. As in that instance, my point is not that we should paint political economy or political analysis in gore-smirched tones to ramp it up. It's that a palette that leans heavily toward the black and red end of the color spectrum is far more likely to give some sense of the mechanisms and relations at stake. The generic parceling off of such appearance and tropes into something called horror is a distancing mechanism, transposing the everyday into more safely delineated shapes that have things like fangs and knives.

The point is, therefore, not to illustrate communist theory with Grand Guignol tricks. It's to understand that dark times call for dark theses. It's to try to become unlike ourselves, to not flee toward the vacancy of the other direction.

And I think a single image will suffice to visually frame this...]

Recently, a British woman was arrested for theft. She had taken spoiling food – primarily meat, specifically ham – thrown out by a Tesco supermarket after a power outage. After her arrest, Mrs. Hall said: "Tesco clearly did not want the food. They dumped it and rather than see it go to waste, I thought I could help feed me and my family for a week or two." However, in the case of Hall and Tesco, the shop said the contents of the bin belonged to them, even though it had been tossed out. And, we should note, Tesco has stated that they work to "minimise waste and where possible will seek to reuse and recycle it.” Of their green measures, most notable is the fact that every year, they send thousands of pounds of leftover meat to be burned for electricity.

Unsurprisingly, property – as relation – is thicker than hunger – as caloric need. And the material fact of having been discarded isn't enough. As a property lawyer commented on the case, "It isn't enough to throw it out. One needs to intend to abandon it.” Although this is wrong, as intention alone won't cover it. It is owned straight through the process of decomposition, until the ham goes green and liquifies, until it pools in a sludge at the bottom of the bin, seeping a bit out into the street on which there are bodies that have little meat and less work. That declaration of property and potential valorization is a form that clings to its object beyond any transformation of matter, barring one: only exchange (only M-C), an exchange between two parties, can affect this belonging. Without circulation, it cannot go properly unowned, even as it goes unvalued, wet and reeking. There is a tie that binds beyond the weave of sarcomere.

All the more as it does not rot but burns: not charred on a grill, not consumed in the furnace of a body, but burned plain and simple. Like the raising of food to be eaten by those who could work, this is caloric expenditure in the name of productive energy, yet without having to route back through living labor and all its complaints and requests. Just straight back into circulation, maintenance, upkeep, and reproduction. Into the electrical circuits, for example, that keep the Tesco lights burning white, to bathe the rest of the unbought meat as if in blue milk, where it waits to be burned and never to be disowned.

It's there, this triangulation between

1) the rotting ham, letting loose caloric energy into an inedible puddle, between 2) her attempt to feed herself and her family, to take in calories in order to keep living, thereby requiring more activity to be undertaken to gather more calories, and between 3) the next batch of meat to come, which will require energy and exertion to maintain it, to get it turned into money, and perhaps energy, before it is fully devalorized,

that I want to address. For the sake of clarity, I'm addressing only a single text at length, namely Marx's 1857-1858 notebooks gathered as the Grundrisse. I'm not interested, in the least, of proving, disproving, or insisting that we need to “go back to”, Marx. Only that the hot mess that is the Grundrisse, inconsistent, wild, and provocative as it remains, is the occasion for these thoughts, although they bear beyond it.

To add a specific framing of my target to the one I share with Ben, it is that tendency which understands our living labor as an originary vital force of praxis and material transformation hemmed in, restrained, and dominated by the form of the wage relation, yet which remains always in excess to it, a boundless potential bent and pent up by the chronometrics and abstractions of value. As my title indicates, I'll approach this via three main notions: labor, form, and meat (or substance, in the less nekro version). As will become clear, I'm not engaging substantivelty with vitalism as a philosophical tradition. I am countering a set of notions that still, after all these years, after all this blithering idiocy we call the last three centuries, want to valorize labor as something worth doing and life something worth dying for.

Let us get back to meat, to a footnote late in the Grundrisse.

"In regard to the reproduction phase (especially circulation time), note that use value itself places limits upon it. Wheat must be reproduced in a year. Perishable things like milk etc. must be reproduced more often. Meat on the hoof does not need to reproduced quite so often, since the animal is alive and hence resists time; but slaughtered meat on the market has to be reproduced in the form of money in the very short time, or it rots."

To be alive - meat on the hoof, rather than just meat (in-itself, if you wish) - is to resist time. To reproduce oneself, as a continuation of a life, is to stave off another reproduction, a reproduction that will liquify frozen form. Rot being the failure of circulation, just as much as not decomposing (i.e. the frozen hoard) would be, in that it isn't a reproduction, transposition, and accumulation, through intitial decomposition, of the value bound in one form into another. Money, of course, is just such a correct liquidation, the necessary one: it's the universal commodity that bridges decomposition and recomposition. More prosaically, it's just a way to keep said meat animated after the fact, to recoup its loss and recuperate its supposed generative potential, via

1. The preservation of the meat: money exchanged for refrigeration, workers to make sure no one shoplifts a rack of beef, butchers to cut into smaller pieces

2. The monetary consumption of the meat: the cash exchanged before the point of no return (the "sell by date"), the meat as a vector or medium for other activities involving money (unwaged work of cooking, energy bought to grill it up)

3. [optional] The physical consumption of the meat: the caloric energy frozen in that meat is processed, albeit by an initial caloric expenditure of chewing and cutting, and thereby reproduces the potential labor-power of the eater. If unused, it will gather in convenient storage units around the thighs and belly.

4. [optional] The application of the meat: that caloric energy gets used by the one who ate it, thereby joining the ex-life of the meat with the life of the human "meat on the hoof" busy resisting time and rot.

As marked by the optional status of the last two, the mode of the meat's destruction is utterly irrelevant, provided that the first two conditions occur. It's "supposed" to get plowed back into circulation not just as money but also as caloric input into the reproduction of a body, preferably one that might do some work. But it does not matter. Only that it has been reproduced. That is to say, utterly transformed.

It might seem, then, that "we" humans are the exception here, not only because we are the source of value. Rather, because we are, in general, they whose reproduction requires a preservation of that existing thing in its distinct life and form (read: body able to sell labor-power, perhaps to actually expend some energy toward a hypothetically productive end, economic subject of getting paid, and point of transfer/proper name through which money flees back into the market). Would that it were so. Our reproduction, as subset of the circulation and accumulation of capital, cares not a whit about the preservation of these specific things, these individual bodies we are.

No: what matters is only the perpetuation of the life of these things in general. That's the core of the difference between living labor and labor-power: it is always a distinct I who does the laboring, but what is exchanged is labor-power as such, in a prescribed duration of time. This is a key difference to be stressed and clarified. As David Harvey puts it,

“There is, in Marx’s theory, therefore, a vital distinction between labor and labor power. ‘labor,” Marx asserts, ‘is the substance, and the immanent measure of value, but has itself no value.’... What the laborer sells to the capitalist is not labor (the substance of value) but labor power – the capacity to realize in commodity form a certain quantity of socially necessary labor time.” (from Limits to Capital, 23)

[I want to mark this reference to the “substance of value” now, because one of my points is to consider the variegation and overdetermination of this substance.]

But if the point drawn out is the gap between the labor performed (a quantity of that universal measure) and the capacity to generate value, this gives a certain optic onto the strength of the historical workers movement, in its apexes and nadirs: namely, in the degree to which it tried to insist on the inseparability of these two things, insisting that labor-power not be understood via a general calculation of the factory's total hours of socially necessary potential surplus-labor but in terms of the concrete labor, the conditions and length of the working days, and the caloric-social requirements of these specific laborers. This is short, to tie labor to the lives of distinct instances of the working class, not the life of the working class – and all those else without reserves – as aggregate.

Yet this direction of the workers movement produced, in its very success (putting the brakes on the continued extension of the working day and thereby absolute surplus value), a major stumbling block: in binding the calculation of the wage to the costs of reproducing those individual workers (and, in certain periods [say, in the US and continental Europe, from the mid-19th century until the 1960s] generally including their wives and children as part of that cost), it forfeited the possibility of a more equivalent and ultimately disruptive caloric calculation. Namely, between the living labor expended and the total costs of the reproduction of that labor power (which, necessarily, includes 1. the continued existence of those who are not employed, as downward pressure on the wage, and 2. the continued existence of those who literally reproduce the species and frequently wipe its asses, namely, women). Such that in insisting on the rights of workers, it necessarily accepted a far lower amount of remuneration than requisite for the continued life of the class.

This isn’t to assert a counter-factual or that to venture that it was historically “possible” to do so, although given the counter-public sphere emerging in the worker’s clubs, self-organized class welfare, and the union in its widest incarnation of the industrial and Fordist period, we can nevertheless glimpse a different trajectory that, in fact, would demands wages for the class as a whole (or of a region or company), rather than for individual workers, an amount that can only be higher than a tally of the plausible wages of those actually employed.

[Such a notion was posed, briefly, in the theoretical output of the Italian long 70s, in the social wage, although ultimately, their obsession with the wage did not serve them well, particularly since what I describe is compelling only insofar as it would be intended to rupture the very category of the wage by the impossibility of this demand, not extend it wider.]

[Such a notion was posed, briefly, in the theoretical output of the Italian long 70s, in the social wage, although ultimately, their obsession with the wage did not serve them well, particularly since what I describe is compelling only insofar as it would be intended to rupture the very category of the wage by the impossibility of this demand, not extend it wider.]

Clearly, none of this came to pass, and therein the disavowal, on the part of the workers movement, of the necessary function for capital of those who do not work and who merely “are alive”: by not focusing on their cause, as part of the calculation of the wage, the workers movement could not adequately conceive of the total costs of reproduction of life, of value, and of the gray areas in between.

However, the impetus remained initially correct for a system in which there are not slaves (i.e. workers as fixed capital). And despite the attempts to yoke together labor-power (as a form in time) with the expendable capacity to work of those who did, or to join together a laboring life with living labor as a mass of exertion irrespective of the divisions of this or that body, it remains a real, structuring separation.

Unlike, say, a bandsaw in factory, which indeed aids in the production of value and the circulation of capital. Yet insofar as it is reproduced/maintained (with electricity, new parts, and living labor poured through it), it is in the name of this particular bandsaw continuing to work and do its job. Because it has already been bought in full, it is in the interest of its owner that this very distinct instantiation of the category of bandsaw keep functioning, as long as it performs competitively. It must, therefore, be cared for. (To telescope, from the the general perspective of capital, though, the sooner it busts, the better.)

I want to pause here, on this saw, and its relation to those who use or get used by it, to mark briefly the relation to automation. This is a far longer account that could be given, but it retains its shape in a sketch. Namely, in my reading of Capital, one born out elsewhere, in the long account given of the development of the full “machinic assemblage” of the factory, Marx lays out out how, initially and in line with formal subsumption, the technology employed was that which didn't fundamentally disrupt the flows of handicraft. It mimed that manual work, an equivalent tool/productive organ to machine of worker + tool, such that the worker still functioned as the “transmission mechanism” and “the motive force”, the latter of which to be quickly replaced by the “Promethean” power of steam and coal behind it.

It is an imitation of labor: once set it motion, the machine “performs with its tools the same operations as the worker formerly did with similar tools.” Yet as more complex factory flows developed, which distanced further from an organization of bodies and materials inherited from craft production, the “similar tool” in question comes to be the laborer herelf, inserted into the machinic process as if mere implement, the pace and rhythm of labor time forced into accordance with that set by the factory. What this means, in short, is that living labor comes to imitate the machine, to ape its speed and patterns. Given that the machine was, first and foremost, an imitation of living labor, factory work is, it turns out, an imitation of an imitation of living labor.

It is an imitation of labor: once set it motion, the machine “performs with its tools the same operations as the worker formerly did with similar tools.” Yet as more complex factory flows developed, which distanced further from an organization of bodies and materials inherited from craft production, the “similar tool” in question comes to be the laborer herelf, inserted into the machinic process as if mere implement, the pace and rhythm of labor time forced into accordance with that set by the factory. What this means, in short, is that living labor comes to imitate the machine, to ape its speed and patterns. Given that the machine was, first and foremost, an imitation of living labor, factory work is, it turns out, an imitation of an imitation of living labor.

In my immediate context, it is the general dynamic that's of particular interest, in which a form of structuring productive time emerges first as a description and imitation of a set of material processes, yet does not remain a labile, recalibrating capture adequate to the heterogeneous material falling beneath its sign. Rather, it unfolds its own formal logic, becoming instead into a structuring abstraction, such that, in this case, machinic labor comes to ape the working of machines that, in their initial incarnation, aped these relatively skilled humans.

In the present context, there are two versions of “giving form” to be brought out, versions which ultimately cannot be separated, least of all into an opposition of active and passive. First, in a rather infamous turn of phrase: “labor is the living, form-giving fire; it is the transitoriness of things, their temporality, as their formation by living time.” (361) Accounts concerned to locate a liberatory potential in the liberation of labor from the constraints of value find much ammo here, as it accords with a general sense of the creative potential to remake the world in our image, such that “all” it would take is to turn productive apparatuses off their current course and into fluid, “nomadic,” experimental applications of our never-fully exhausted capacity to give form in time.

Second: “labor also is consumed by being employed, set into motion, and a certain amount of the worker's muscular force etc. is thus expended, so that he exhausts himself. But labor is not only consumed, but also at the same time fixed, converted from the form of activity into the form of the object; materialized; as a modification of the object, it modifies its own form and changes from activity to being.” (300) This description, of the development of the product as frozen concretion, is not opposed to the first formal mode of labor, insofar as it represents a turn of the dialectical screw and insofar as it gives backing to that line of argument which understand the first mode as primary or originary, falsely captured by the commodity form and its material output.

However, there is, in Marx, another way to grasp the emergence of form that comes closer to articulating the fundamental tendency of what Sohn-Rethel understood as “real abstraction”. Take the rather notorious example from The Poverty of Philosophy. Marx writes, “Time is everything, man is nothing; he is, at the most, time's carcass.” This appears, initially, as just a conveniently catastrophic metaphor. However, two relevant interpretations.

1. In the loosest and more standard interpretation, that takes it primarily as a ramped up modifer of the preceding sentence concerning how “one man during an hour is worth just as much as another man during an hour,” man is “time’s carcass” in that man’s specificity is killed, leaving man a carcass animated by value and made to labor, simply a material unit of potential activity subordinated to labor time. Man is as if dead labor.

2. If we recall the particular dialectic of form and content in Marx, we approach a different perspective. The active development, via the laboring of man as labor power (the content) produces the material conditions for labor time (the form). However, the perversity of capital is that this form does not remain adequate to its content. It becomes divorced from it and increasingly autonomous. But this is not the story of a form that simply takes leave from its content and “becomes everything,” merely dominant. Rather, it comes to determine the content in a relentless passage back and forth, to force it to accord with the divorced development of that form, such that any opposition between form and content becomes increasingly incoherent. As such, man is time’s carcass in that labor power is valued only in accordance with its form: it is that formal relation of exchange, fully developed into the general equivalence of value, alone which is of worth. Man, as that which labor, as the material grounding of that form, is a husk dominated by an abstraction with no single inventor. Form fully reenters and occupies the content as if it were dead matter, rendering it incapable of generating further adequate forms. And when it is productive to do so, time makes those bones dance.

Very well: what of that carcass? What of this substance? As mentioned previously, and throughout Marx's work, the most common notion of the “substance of value” is labor (as unspecified living or objectified): the most general substance which, in terms of labor time, forms the measure of all value. Substance is an unruly and slippery notion in Marx's thought, though: consider elsewhere in the Grundrisse, where money is both Gemeinswesen (real community) and the “general substance of survival” (225). More widely, substance is, I'd argue, one of the ways that Marx is able to think through an impasse in thought, an impasse that gives fundamental shape to the relations of capital: how are we to square capital's indifference to particular material form while nevertheless producing a set of limits and strictures in which the range of formal expressions of matter are, on the one hand, radically heterogeneous and, on the other, utterly interchangeable? Substance is the subtending that allows this emergence and flattening, the realm of formal potential and potential forms.

In the Grundrisse, though, there are two notions of substance raised powerfully. First, there is:

“The communal substance of all commodities, i.e. their substance not as material stuff, as physical character, but their communal substance as commodities and hence exchange values, is this, that they are objectified labor.” (271-272)

While the determination is not material, and their character not physical (because it is the quality of being past labor, hence a temporal fact of a duration of once-labor persisting into the present), it appears in that present as as “present in space,” as opposed to living labor which is “present in time.” Space-time turns out to be, then, just degrees of living labor. However, labor – in the present – cannot sustain itself untethered from something that lives, for it must be present not as a mass of labor (that would be objectified/dead labor) but as a present capacity:

“If it is to be present in time, alive, then it can be present only as the living subject, in which it exits as a capacity, as possibility; hence as worker.” (272)

Immediately, though, this raises the prospect of another substance: the one that makes up that worker in question, who is, at first glance, not exactly just an accretion of labor. There is, then, a second general substance:

“For the use value which he offers exists only as an ability, a capacity of his bodily existence; has no existence apart from that. The labor objectified in that use value is the objectified labor necessary bodily to maintain not only the general substance in which his labor power exists, i.e. the worker himself, but also that required to modify this general substance so as to develop its particular capacity.” (282-283)

The second substance at hand is that of the flesh and bones of the worker, quite literally: the bodily frame that is the medium, matter, and basic content to be developed/shape/betrayed by the specific forms living labor takes. However, we should account for the precise relationship between these two substances, and this is an aspect that I've yet to make explicit. Namely, that the real purpose of living labor is to preserve, maintain, and animate the dead, or objectified/past living labor, that absorbs it. Living labor is employed in that race against time and rot. For left alone, objectified living labor is a “mere thing at the prey of processes of chemical decay.” In a crucial passage:

“The dissolution to which its substance [here meaning literal material that can decay] is prey therefore dissolves the form [material form, and, in this case, form of value value] as well. However, when they are posited as conditions of living labor, they are themselves reanimated. Objectified labor ceases to exist in a dead state as an external, indifferent form on the substance, because it is itself again posited as a moment of living labor.” (360)

The point, then, is not merely that living labor reawakens the value embedded in objectified labor (as raw materials and instruments of production which transfer value across the duration of their use or consumption): that is, not just a relation of present labor toward past labor. It goes in the other direction as well, as objectified labor is posited, materially, as a “moment of living labor.” Elsewhere, Marx speaks of this as the “living quality of preserving objectified labor time by using it as the objective condition of living labor in the production process” (364). In short, the condition of living labor, which “preserves the material in a definite form, and subjugates the transformation of the material to the purpose of labor,” is that dead labor as such. So while living labor “add a new value to the old one, maintains, eternizes it” (365), it is far from a unidirectional process. Rather, there is a total collapse of the dividing wall between the two zones: the process of production is an indistinct muddling of living and dead labor.

What I want to propose is that we can start to venture a third general substance, between that of the worker (that baseline of literal flesh) and that of value (i.e. the product of already objectified living labor). This third general substance, which is the meat of my argument, is the terrain of living labor as the impossible mediation – a relation, formalized in the shape of labor-power – between the two. It is, in short, the expenditure of life in the name of holding off the rotting of life already spent. It is an immanent relation, with an increasingly blurry line, of living labor to itself in two modes: objectified and present. It incorporates, at once, those two other general substances: the reproducing bodies of the working class and the materially fixed remainders of past labor which needs constant reproduction, in terms of a) maintenance, b) living labor as transmission mechanism and source of surplus value, or c) complete transfer of value across an extended period of production.

[Let me note quickly that this is not just a problem for meat theorists: it also represents a difficulty for political economy, in the calculation of the value composition of capital. Namely, at what point in the production cycle do you stop considering living labor – with its rate of surplus-value – living? As these two charts borrowed from Harvey's Limits to Capital show, we get a very different portrait of the composition [fixed vs. relative capital] if a commodity is produced entirely in one plant as opposed to passing between industries.]

Here we can double back around toward some crucial general positions.

- Recall first that what is particular about the generative power of living labor is not that it produces more use-values, or that it bears any resemblance other than coincidence to the production of materials that would help it live. The point of living labor is that it produces surplus value. As such, when considered in terms of this third general substance (that is, living labor as a total medium, in the present but including the full range of accreted values and labor required presently to reawaken them), we gain a very different portrait of living labor, that cuts against the dominant fantasy of it as a generative potential to be freed from the regime of value. Namely, it is living labor not because it is active, and not because those who labor are living. It is because it makes what is already dead almost live again.

- Of course, this substance involves things that seem – at least politically and juridically – very different: living human beings and “dead” non-human material.

And it is there we see just how they relate, and the inversion of care for those things. For while it matters that the objectified living labor already present in the factory be maintained in its particularity (this machine, this pile of once living labor, in which capital is already invested), for living laborers, this is flatly not the case, from either a local or system-wide perspective. It is of no grand importance if a particular one breaks down, and it just slows down circulation to have to keep it running (via the insistence of political pressures to keep manufacturing at home, via the rarer insistence of other workers to strike if this busted one is not given a modicum of attention or remuneration). Especially when there are new, cheaper models elsewhere (read: Asia, Latin America, the global South). What matters is the reproduction of labor-power in general, both in its local instance (the labor pool in a particular zone) and in its global scale (the hypothetically employable portion of the species). So while it demands there be particular workers (obviously, there can be no such thing as labor-power, and hence no surplus labor, without laborers), it is opposed, violently, to them in their particularity.

Instead, it is only in the name of that human in general. And in a very, very perverse analogue to the incorrect demand that communism be the flowering of the universal or the common, the reproduction and requirement of living labor is in the name of a) past life of the collective [the maintenance and remobilization of a mass of living labor already past but not gone], and b) life to come [ the general expansion of the ranks of the species, I.e things that could contribute living labor],

But it is directly – and far from accidentally – opposed to the upkeep of the individual humans who make up part of the species that labors productively, and it is opposed to the continued animation of the individual humans that make up the other part that does not produce value. All this is to say, living labor is literally, not figuratively, opposed to particular lives. Unfortunate, then, that we know no other way to live. For it is in the name only of a generalized life, a substance that is, ultimately, like our meat, off the hoof but not yet off the hook, required to keep hustling.

So if there is any “life” to speak of here, it is first and foremost surplus-life: too much of it, and incapable, coerced, badgered into keeping itself still fresh, in pretending that it, like that bin of ham, could still be sold. I've written about this elsewhere, in a context I don't particularly want to breach today, namely, films of the undead, specifically about zombies, for the basic reason that I'm sick of that topic. But the structural condition I detected in those films remains relevant. That is, what drives especially the genre-founding films of George Romero isn't that the dead suddenly come back to life, nor is it that all that have ever died stand up, a rather literally earth-shattering prospect. Rather, there is an unnoticed event that effects the totality, that brings about a new general state of affairs, after which the living will not stay dead, cannot truly die. In short, the fundamental problem of the films is that of surplus-life, not the living dead. It is the conatus gone haywire.

The connection more broadly with horror as a genre and mode, particularly when concerned around the practice and figure of the economic misuse of the body, deserves two further points.

- The strongest versions of labor horror have not been those openly focused on the contradictions and brutality of capital as such: they have either been allied to state socialism (Platonov, Pilnyak, Müller), to mechanized warfare (Walter Owen's criminally underread Cross of Carl, in which a British man left dead on the battlefields is bundled up to be salvaged in a rendering plant that will plow the dead back into the war effort; elsewhere, David Jones' In Parenthesis, Kurzio Malaparte), or “technology” as a self-determining force of domination (a good half of robot and cyborg oriented horror, Tobe Hooper's The Mangler). The full hostility of dead labor, in films from the heart of developed capitalism, have been best articulated in slapstick (see here Buster Keaton's Steamboat Bill, Jr.) or, and this is my temporary focus today, on the figure of the cannibal or the butcher (Texas Chainsaw Massacre, for instance, in which they find a creative solution to three things at once, a meat shortage, an influx of lost teens, and the loss of their jobs.)

- However,what's at stake in this horror of the cannibal is not so much disgust, in Baumgarten's sense, of the proximity and incorporation into the body of the excresent or dead, and still less some violation of a fundamental taboo. Rather, it is in the thought that one's dead body will not be given the chance to simply rot away, to finally sever itself from the third substance. Instead, it will contribute to the reproduction – calorically, and potentially in terms of monetary exchange – of the species and the capital relation.

It's for this reason I've spoken of meat. For as opposed to flesh, meat designates that which is not alive, yet which is destined, or intended, to participate in the reproduction of life: it is to be consumed. More than that, the word is linked etymologically to the notion of measure: it is, in this way, the general substance of labor living and lived, in various degrees of animation, across which our time is splayed out. We're part of an order of being in which it is neither the reproduction of what resists time nor the suspended pseudo-animation of that poised between rot or money: rather, it is the continual reproduction of slaughtered meat.

Regarding the “political stakes,” I want to buck the natural progression of this kind of argument in which I would give some prescription for communist thought, or, far worse, for “the left.” I won't do that, in part because I doubt that a unified meat theory is unlikely to find much popular support, in part because the conclusions that follow, I believe, point not to how we'd like things to go but to a central blockage of our epoch. As such, it resists prescription.

In this sense, then, the “political” upshot of my comments can be only that it's high time to further sever the ties between labor and communist thought. Not because those who work are remotely excluded from real struggles of seizure and appropriation. Rather, because insofar as communism bears a relationship and commitment to any sense of “life” that isn't merely plowed back into circuits of reproduction, it bears it to a fully contradictory life that insists on the end products of the labor relation - we want food, we want roofs, we want medicine – yet which refuses to play the dwindling game of living labor. It is the imposition of communist measures, not because they are theoretically correct, but because other measures show themselves to be voided of adequacy and effectivity, capable only of replicating the very bonds that necessitate such a severing to start. Whatever we mean by communism certainly won't be a new mode of production, and not a new society either. The only sure thing is that it will be very messy.

I want to end elsewhere, though, further back in the 19th century than the Grundrisse, with Byron's “Song to the Luddites,” sent in a letter to Thomas Moore on December 24, 1816:

. . . Are you not near the Luddites? By the Lord! If there's a row, but I'll be among ye! How go on the weavers--the breakers of frames--the Lutherans of politics--the reformers?

As the Liberty lads o'er the sea

Bought their freedom, and cheaply, with blood,

So we, boys, we

Will die fighting, or live free,

And down with all kings but King Ludd!

When the web that we weave is complete,

And the shuttle exchanged for the sword,

We will fling the winding-sheet

O'er the despot at our feet,

And dye it deep in the gore he has pour'd.

Though black as his heart its hue,

Since his veins are corrupted to mud,

Yet this is the dew

Which the tree shall renew

Of Liberty, planted by Ludd!

Of course, if we read with a close eye, what is the actual horror here? It's the slipping hinge between "the gore he has pour'd" and the "black" heart of the machine/despot, with its "veins corrupted to mud."

That is, the dyeing of the shroud - black - is done in the gore already spilled (read: that of lives destroyed in the course of being employed as living labor), not in that of the slain master. The shroud is not oil-slicked. No, it is dyed in the dying that had been happening, such that even at the point of the despot/machine's death, it lies cloaked in the winding-sheet that was the very product it made all along. From absorption of labor power, in the name of production, to the sopping up of life lost, in the name of the mocking burial of what never lived.

But if it is not its blood but our own in which it is dyed, then we too must have those same black hearts (“Though black as his heart is its hue”), that busted pump that shoves our cheap gore around worked veins, the same general flesh of labor. To truly exchange shuttle for swords, we lay ourselves down next to the slain machine, pulling the wet shroud over us all, tuck us all in, and open a vein.

Let the living bury themselves as, and with, their dead.