R,

A wall is covered with a thousand ilia. They are creeping, nestled wings and they do not ripple in the wind and there is no wind.

Other than the joining exhalation of mango-flavored lip gloss and centuries of musty rot, that is.

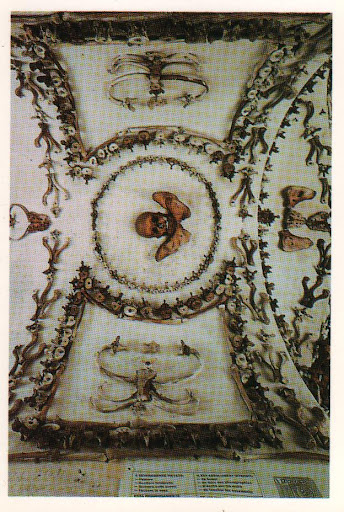

I'm in the Capuchin Crypt, near Piazza Barberi, where you go up two flights of stairs and down three, and the complete skeletal systems of four thousand friars are stuck to the walls, ceilings, arches, femurs stacked like thin cordwood, careless worn skulls, polished by 30 years in the dirt before dug back up and pulled off the body.

And a single skull is tacked in flight, on scapula wings, to the ceiling.

Below it there crowds one of the worst gatherings the human species is capable of: forty-three German pre-teen tourists, teetering on the earlier edge of puberty. They reek of shampoo and decades of mediocrity to come, and all of them are wearing matching red scarves knotted around their necks so they can be identified when they wander off down darker corridors to try to make out and fumble the hinges off an unnecessary bra. They are pink-cheeked and bleach-tipped and the little shit next to me absolutely will not take off his sunglasses.

They are filing past an arch of pelvises, stripped of dicks and flesh, like dinosaur heads but without tendons and testicles.

Bone flowers everywhere, repeating loops and sprays of hard yellow calcium. Jumbled bodies, a mass grave made into wallpaper and folly. A Todesspiel.

On the wall is written:

Il mondo come noi lo conosciamo sta passando

The world as we know it is passing

The crucial point is that it's passing, not past: this isn't the friars' lament from beyond the grave in which they don't rest. This is the bones talking, the same thing they say when surrounded by a body that lives as when surrounded by a nailed cluster of other ribs that have no corpses. The knowing of world, as bones know it, is a passage, an order and arrangement, a set of structural distances and negative space against gravity Whether that means the supportable weight of a span between metatarsals or the correct distance those same bones to spell out a rhythm that doesn't move and sits to remind sweaty adolescents that their ripe loins too will rot.

The crypt protects against such thinking and then it goes on to dismantle its own protection.

For there is a concession to guard some principle of the unified body's coherence, as if a body – rather than the scattered bits and pieces of some bodies – was still the ruling measure here amongst these flurries without meat. Hence the insistence on keeping the few full skeletons, with their dusty brown robes and hoods draping low over the teeth that don't have gums and this is supposed to ward off the fact of everything else, of coming undone into the more monstrous particulars, or it can bolster the stated pedagogical function – to remind us of our transience, hence we should get good with God because all our vanity will come to naught, or at be relegated to one slightly more attractive ulna than the rest of hundreds fanning out – by providing a midpoint in the dissembling. Ruddy cheeked biscuit-fed tourists carrying guidebooks : hunched skeletal friars : five-hundred and eighty-one foramen obturators dotting the wall like snow.

Or there are figures we know: an hourglass, a scythe, and yes, they are formed from things that are not glass and metal. That curving blade is a cobbled together set of scapule, and we turn to those in front of us, start taking them apart in our sight, envisioning his skull a goblet, her leg a cane, not to be whittled and fashioned but all along, these things as finding their form only after the death of the one who carries them. The bones lose origin, because when you crook your head, yes, there is something clock-like there in you, and now you are not a man, you are just a rather chubby cargo shorts-wearing clock waiting to be stripped down.

But all this still implies design for: the full body designed to carry upright, the proper fit of bone to approximate a known figure or to be gripped by another hand. A reaper who needs no scythe, just puts shoulder to ground, wheat, neck.

But then, but then there's the fact that the body contains 206 bones.

And where the crypt starts to come apart, where it undoes the centrality of the body as ordering device, as thing to be held or lost, is this principle of completion, that when a body falls down and the skin peels away, you aren't left with just a skull to hold and polish, or a couple femurs to cross below it.

And there are 4,000 dead friars. And 824,000 bones.

What to do with 4,000 scaphoid bones, which are not allegories or signs? We cannot look from them to our wrist and think, oh yes, that belonged to someone as this little piece does to me, and oh, mortality, you cruel master. I stood and looked over these bones and I did not know where they belonged, if they helped hands turn pages or asses hang over holes or teeth crack through other little bones.

The need to use every bit renders the bits inhuman.

At most they become animals, fossil echoes.

The sacrum is a hollow turtle and they are everywhere.

Lower jaws are paired with each other, which means they are transformed into shark jaws, with the teeth facing wrongly.

Bent wings of clavicles swooping low.

Though these are the exceptions, the searching eye finding something that sticks, like looking toward clouds.

Above all, it does not work, and the dissembled bones are just ornament, faced with total non-figuration and non-recognition. We ask only what the hell is this bone, we have to reach it with the double knowledge that it belonged to a body and that it cannot be known as such for it is simply an architectural detail.

Even when the three full friars are propped up in front of us, like a weak haunted house, where their grimacing skulls are supposed to draw the eye, sight wanders and they are standing below arches of vertabrae, from other countless bodies and there is nothing horrible in the full clothed skinny men, only perhaps in the fact that they come to mean so absolutely nothing beneath and between this frenzy of figureless detail.

Walls of dots of padellas, wavering polka dots.

The hooked socket of the ischeum.

The different speeds of the vertebrae, a pacing, halting wave alternating thoracic and cocygeal.

A blunt chipped tarsal period.

Vile hooks of rib broken from the cage.

In the furthest room, the one set sequentially as last, there's a small sign posted at the center. It reads:

QUELLE CHE VOI SIETE

NOI ERAVAMO;

QUELLO CHE NOI SIAMO

VOI SARETE

What you are

We were;

What we are

You will be

Next to me, this dismal tourist couple – dressed, because they are American, in clothing far too technical and ready for long-term desert trekking than is necessary for wandering from church to cafe in Rome, but that's what Americans do, because they like to imagine all of their trips as excursions – snuggle and he says, that's a good reminder, isn't it honey? and they have a reassuring kiss and they actually will remember this moment and say, you know, it really put things into perspective, you just have to appreciate what you have before it's gone, while we can still be what we are, not were, still wear sandals and spoon each other in the night with the AC blasting cold so we feel like we need the warmth of another body.

Chatelain wrote of this place:

and what appears to me yet more disgusting is that these remains of the dead are only exposed in this manner for the sake of levying a tax on the imbecility of the living

He's right on one count, wrong on two: the imbecility of the living is in full gawking bloom, texting their friends while feeling sweat dry on their clammy knee-backs and hoping to cop a feel. But it's basically free these days and what taxes, if not money, isn't the other side, the supposed confrontation between the living and the dead.

A confrontation that cannot occur, as the forces are so dissimilar as to stare dumbly past each other. How does a German tween in a apple-green polo shirt look at a skeletal baby stuck to the ceiling that is not the bones of a baby, but a borrowing of the smaller bones of an adult, so that a rib is not a rib, but something small and ribbish enough?

And this is what horror gets wrong, or at least the way we tend to talk about the horror of sights like these, which wants to imagine the node of the horror effect as the consequence of a speculative leap, of being complete and constant, and aware of that fact, past the point of life. I know now that I will be a skeleton, I will be dry and empty, and what's so bad is that the little word – I – sticks straight through. That's the flat awfulness the clutching couple thought they spoke of.

But that's not it, of course. It's the wrong use that's worse. It has nothing to do with death. Only with misplacement, or worse still, perfect placement.

Not that you'll be dead, not that you'll be forgotten, but that you'll be employed, un-wholely, in a design beyond you, that cares not a whit for some I that was planning to persist and now finds itself parceled out into 206 potential serifs, rays, arcs, sprays, points, and curls.

And what is this if not the basic fact of economy itself, in which we are waste to be managed, in which even the unimportant bits get squeezed and turned, made into value? By value, we mean: that claims its worth on the ground of that dismantled I yet which is utterly hostile to it. Which doesn't build the forms from scratch or wait for something to decompose into usable chunks but which eyes hungry what is already the other thing it could be: engine, clock, hour, tendon, axe, sweep, delay, glue.

And it hisses, like dry steam, the missing line

What you are now, we are now

That is, a collection of objects, teetering on failure, the woodpile gnawed from the inside out.

An organization dreamt of as utilitarian, all things built for their purpose, but so too these lesser bones, which join and hook together to soar low, these bones that do not belong to anything more than this.

We are already these things, not just because we're dying from the start, not because we're a war against rot, which we may well be, but more because the bones urge to be useless, to be ornament, and they urge toward something else, something more vicious that we call value and that means nothing other than that whirring tangle of scalpel and glue, which itself founds a urge to find that place for them, in the tired sweep toward making more of this world, of making sure that what we are now is what we will be and have been then.

Anyone who talks of totality must talk ultimately of this. The recognition that it is no longer about the single clavicle that matters and that maybe we break or someone digs clutching at when fucking or over which a necklace might rise and drop, but only the horde of them all, coming and fixing together in arching curves. They write in cursive and say no thing.

Yours

E

2 comments:

You crack me up, Evan. I read an article titled "Evidence of Things Not Seen: Virtual Reality and Sacred Spaces"-- which of course turned out to be significantly less interesting than the title suggested-- and it reminded me of International Cyberpunk and eventually of your blog. Hope you are enjoying your travels.

E,

When you spoke I fell.

This searching eye looks towards clouds that have already shattered. Now only an echo suspends from this wall of letters. The bones of which you speak wish to take flight, desperate to talk of time alone. But how to talk if above all I am broken? What to speak of? Without direction, I am no more. At peace and still with hunger, we simply wonder where to lie.

- Felicia

Post a Comment