I start with what may seem a double disappointment for introducing a futurish high fashion war of the sexes, a black comedy about the bullets and saliva traded back and forth between two assassins assigned to kill each other in the "Big Hunt" competition: I'm not going to say much about fashion. And I'm not going to say much about sex.

The former, in part, because the film so foregrounds this that it will talk plenty about it itself, and because there are some here who can tell me more about it than I'll ever hope or aim to know.

The latter, in part, because despite the ways in which this film plays at being an exploitation film there to give you the goods (the sheer startling physical fact of Ursula Andress makes this the case), it's a film about the endless deferral of getting the goods in which the prospect of cashing out never quite comes to pass, as the money passes straight through your name to the hands of your ex-wife, into a set of endlessly replaceable clothes that are not discernibly enjoyed, at most instrumentalized, into a choice of ready-made full-life furniture settings, into a game that may kill you but that has no stakes whatsoever.

That's to say, this is a film about credit. On death, sex, and ultra-modernism on the installment plan. Or rather, after the installment plan, a presaged vision of the inconsequential plenitude to come. This is a “future” film not only because it is replete with the futurish look of a certain derivation of the Italian-cosmopolitan 60s – a fact that, ultimately, marks it all the more in a present – but because if the film gave us a full info-dump (i.e. when a character or narrator laboriously explains how the future world came to be, which bombs fell or technological breakthrough led to rampaging robots), if it gave us that, it might very simply say: well, the 70s happened. Well, there were crises and fuel shortages and there were people who called themselves communists and did things like burn banks and take over factories. And there was a time when it seemed like this might not get better, as if certain deep tendencies of how the whole infernal apparatus worked would become as indelibly and idiotically visible as they have long been.

But we got over all that. Can we interest you in a line of credit? And should you want to swap out mass violence for trading potshots with other impeccably dressed sexy ones in an execution proto-edition of Survivor, so much the better.

Let me back up. The film we're going to watch is from 1965. The director is Elio Petri, not only one of the most underrated and underwatched Italian directors, from an American perspective, but one of the best political filmmakers of the century: always fierce, always misanthropic, often paranoid, always complicated and without clear resolution, and always didactic in the best way, in that it gives no injunctions of what to do other than to begin in the utter messiness of a struggle that started without you. In this case, we face a film that's often considered more as a sexy, jazzy romp with some low-level critique of consumerism, greed, sexual relations, and the general barbarism of society at large. That's off: sexy and jazzy as this may be, this is not a easily swallowable bit of pseudo-critical film. The razor edge of Petri's political thought isn't dulled here, just buried inside a hip late modernist apple. And it cuts all the more for that.

It stars, in a flawless pairing, Ursula Andress and Marcello Mastroianni, it features a Pierro Piccioni score for which I apologize in advance, because it will haunt your head terribly, and yes, there are those costumes, designed by Giulio Coltellacci in collaboration with the Sorelle Fontana fashion house. It's based on a Robert Sheckley sci-fi short story (“The Seventh Victim”) with some noticeable differences in emphasis to which I'll return.

It is, in brief, the story of a society on the skids that's figured out how to control that drift through a game. Faced with continual upsurges of violence, our not-named near future (Hitler is still given the example of what could have been avoided had the “Big Hunt” been around) confronts two possibilities: either violence happens because the current economic and social arrangement conditions it, (very much including the deep fuckedness of gender dynamics, particularly in its allegedly monogamous married form), or because people are just like that. Given the structural incapacity to think about the former, the ruling order designs the Big Hunt.

You'll get the details straight off in the film, but in short: you can sign up for a competition in which you must survive ten rounds of being alternately hunter or hunted, in which you are legally sanctioned to kill, in whatever manner possible and hopefully with as much flair as the law allows, your designated target. The only difference between hunter and hunted being that the hunter is given full information about the hunted, while the hunted simply receives notice: your life is on the line. One cannot just survive. A hunted must kill a hunter, otherwise it's a life on the run. Make the kill, make some money, make it through ten rounds, and you become a “decathlete,” win one million dollars, a number of product endorsements, and general celebrity.

All supposedly to give an outlet to the basic brutality of human nature. In the Sheckley story, in a manner much more explicit than in this film, there is a basic utility to the auto-destruction of “those kind of people”, as if the point of the hunt was to drag the genepool for its murderous weeds. Here there's something else happening, where it's presumed that everyone has got a bit of this, and, in proper Adornian fashion, they libidinally displace their inaction onto the celebrity decathletes. But the shadow of the other reason why people do this – capitalism rewards nastiness – lingers, and as such, the hunt is both a way of avoiding the confrontation with the social order and a consequence of what happens when the possibility of such a confrontation has been swept away. One of Petri's other films is titled We Still Kill the Old Way. That might ground title for this too: We Still Kill the Old Way, But Now It's Legal.

What I want to ask, though, is what goes beyond this sort of basic sense of allegory, that nodding understanding that, yes, you show a future in order to “really be about the present.” Because given the film's release in '65, there are some aspects of it that were not yet fully materialized, elements of the years and decades to come, in which what it jokingly points toward became a real curse of a "pointing forward", a deferral onto a future payback, that came to structure more and more of social life.

So let's ask of this future: What kind of future (what does it look like), what's underpinning this, and why?

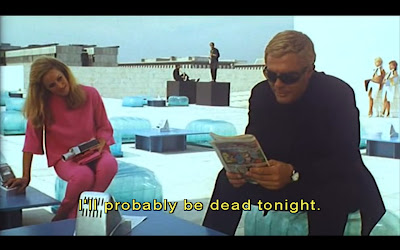

What does it look like, then? Here we get into the side of things that occasion it being watched here, namely, the style of it, its futurist look. Or rather, as I'd prefer to call it, to differentiate from either a certain historical avant-garde tradition or from a sense of being concerned visually with a serious consideration of what might be to come, its futurish look. There is a lot of white, both buildings and fabric. A rough adherence to either boxy right angles (when long walls or incongruous furniture or popped collars), snug black outfits halfway between Italian tailoring and latex fucksuits, bursts of neon, unnecessary bits of fabric (see her entirely superfluous head strap there to help keep the sunglasses on). But not all things look this way. People are still flying Pan Am, the cars are no different, the robots we see are cobbled together more than a bit DIY, and above all, not everyone has gotten the word that you're supposed to wear Courrèges.

Regarding this last point, we should note the way that a) not everyone is clad in such fashion, and b) more forcefully, the version of the future on-display is not an imagining internal to the film itself. Rather, it is a historically marked “futurish” style, tied specifically to Courrèges and others, such that the wearing of it – by those who make of it a project – is distinctly not of the future, but of that mid 60s moment. And in this way, the parts of the film that look most “futurish” are the parts that have the least to do with the future, belonging instead to a very distinct moment in which one could demarcate oneself as being savvier than thou by wearing clothes that do not button, that look like they were made of oil at some point, that cling and hug and hypothetically have distinct fabric qualities that might block UV rays or go from day to neon glaring night without missing a beat. But reading them as of the future would doubly miss the point. We've had 45 years since then, and we're no closer to wearing neoprene bodysuits as a general population. And such clothes never belonged to a different project of designing for a mode of future life in which such concerns for utility would come to rule the day.

Two brief points on this overperfomance of the future.

First, when you meet the central computers in Geneva (the echoes of Swiss banks are utterly unmistakable) and they read out their newest hunter/hunted match in staccato tone to an empty room, we register that if things are really that advanced, a rough approximation of normal talking cadence should be one of the first things a supercomputer could pull off. Rather, in trying to sound like it belongs to the future, it casts itself all the more back onto a period we've left far behind.

Second, a small note: when Ursula Andress' character reveals why a bullet has not in fact killed her, it isn't because she's wearing a teddy made of a carbon fiber weave with titanium supports. It's because she has a damn good set of “leather undergarments,” a remnant of craft fashion that gets the job done when no number of shining white polymer dresses can do the trick.

What's underpinning this future? I've hinted before: it is the structure of credit, of banking on outcomes, of insurance and deferral. Such an account deserves more time than I can give it, and as such, I'll just gesture here, in a way that the watching of the film itself will fully bear out, that the support system for this order to come has little do with a restraining of the basic human urge to murder, and everything to do with those computers in Geneva, with this death on a prescribed plan, and above all, with the decoupling of credit and wealth from a sense that real wealth is held by anyone, other than the confidence, performance, and promise of paying back. All the more in a time when what matters is not a settling of accounts and a cashing out, but a general precarity, a living off borrowed time and living with things that you bought on credit.

Tellingly, Marcello – one of the more feted hunters in the game, albeit a bit past his prime and not quite top mark – has zero money to his name, who finds his account drained by his ex wife and unable to do anything about it, who hasn't paid his doctor or coach in a long while, who likely won't make it much longer, yet in whose name an entire new set of chic furniture can be ordered the moment his previous set is repossessed. If the film exists in the future, it is a very near future, in the immediate decades to follow '65, after the dollar is decoupled from the gold standard and becomes the sole backing in a world of floating currencies, after manufacturing stops making so much cash, and after capital starts figuring out how to buy and bide time by extending credit to those who will never be able to pay it back.

To the third question: why is this all the case? The answer the film gives throws it back on the more superficial terrain that it gives, even as it undermines it: it's a fucked up love story. But not just between Marcello and Ursula, not just between the two assassins who meet their match and who are doomed to keep trying to kill one another, albeit with a weary tenderness. Rather, between what we might call capital and labor, or, more anthropically, between classes, not because she seems better off and he's stuck hustling, but because the very dislocation of this type of conflict onto an individual, managed, and, in this film, murderous flirtation type of conflict itself refracts a story about what happened in that period following this film.

In short, in the time when Italy got hot and radical, when it started asking not the older question of why the world under capitalism is so vicious but rather how such a world is composed, how it wasn't remotely a narrative of top-down imposition of power from a state but an awful love story of dependence and desperation. Of how those who had struggled to kill their opponent often made it stronger, of how the constant back and forth of gaining and losing an upper hand lead, increasingly, to a situation far bloodier and with far less motion, as the 70s bled out into the 80s and neoliberalism beyond.

This isn't just a projection on my part because I think that all films should be read this way: a cursory glance at Petri's other films and, more than that, the historical situation of Italy shows us a time when insurrection was both talked about and attempted, when people stopped going to the cinema as often for being caught in a terrorist bomb blast, and when the sharper thinkers on the left started realizing that the real question wasn't how do we stick it to you? But maybe we should start seeing other people, that what had to broken was this deadlock of perpetuation, of feeling like you're the hunter on top for a bit, knowing damn well that come next round, the general structure – credit, value – that dictates the whole thing will be in place and that it'll be your turn to feel harrowed and on the run. How fitting that the scene of the first murder is The Masoch Club, perhaps not just a cute joke on how disaffected this future time of jaded murder viewers are, but a real sense of how class antagonism is reduced to a cycle that revolves but with no revolution. A melodrama of stale antagonism for the era of easily available consumer credit to come.

This film series falls under the sign of melodrama, and such a designation gives another way in to what's at stake in The 10th Victim. What, then, is meant by melodrama? At the heart of it lies a two-fold logic: that of excess and that of sentimentality, of an inherited structure that is supposed to have real effects (i.e. romantic weepy situations making you weep) that no longer produces those effects in a “natural”, fleshed out way, such that you go through the motions, all the more figuratively and gesturally, hollow and acting out.

The connection here to what I raised about both futurish fashion (you don't produce the effect of the future, you simply turn up the volume on the stale signifiers of that) and about radical collective violence (you don't produce effects on a future arrangement of things, you just parcel that violence out into a legitimated self-perpetuating structure) should be relatively obvious. This is a melodramatic film because it depicts an objectively melodramatic world, one that is crowded with excess but that does not cohere, and that demands of its subjects that they feel something for which they haven't been given “adequate” preparation.

Rather, it is a tentative, searching, genuinely perplexed and misplaced, genuine confusion of what one is to with affect and desire, particularly when that desire isn't just – or isn't much at all – to fuck your deathmate but to fuck over the terrible world in which you live, that awful, rabid, unstable, shrill world of credit and banks, of rules and promotional opportunities, of marriages and furniture. It is that which cannot be figured, which can only be displaced into a restricted set of individuals to kill, into the hostility of love, into a managed war of the sexes.

The second point about melodrama is that I think what gets called melodrama – that strange hybrid of ineffective forms which resorts to manipulative measures to get its audience to feel what those forms can no longer produce on their own – is a crucial underground legacy running through the culture of late capitalism. We might to return to debates about “modernism” or “realism” here, but we don't need to.

Rather, we can just say that if some of the fights about such a thing was about the tension between a fractured style intended to mirror the fracturing of experience as opposed to a more coherent style capable of mapping the wider social world and processes by which subjects came to be fractured like that, melodrama not only points a third way, it also points a certain historical direction – and associated ways of feeling – without which the last century and this one cannot be understood. That is a direction, and structure, of credit, of expectation, of a promised outcome that will not happen other than through the betting on, and borrowing against, the possibility of it being the case.

And credit here means not some imposed financial structure from above, as if you could blame such a thing on some one, but a general condition, a general relationship that comes to infect and stain all things: how people think about sexual relations (consider Marcello's mistress' insistence that she has invested a lot of time in this relationship and she will kill him before she lets him default on their marriage-to-be, the future guarantee of security against which she leveraged her fucking of a married man).

How people think about clothing: one, but not everyone, invests in a present vision of what the future may be both to differentiate oneself (to profit from foresight) and to bring about the future conditions in which such a future sense may be regarded as presently compelling.

How people think about lived space: the line of credit stretched out and frozen, briefly, into a set of objects that surround you, the repossession of which is no problem, given that credit extends its arms longer than the repo man and you call up immediately and order a new set, because when you answer the question “how will we pay for this” with the future profits of one making a killing in the future, no one can say no.

How people think about history: marked out in a series of gestures that mark out the worst love story ever told, of capital and labor, in its distinctly late 20th century garb, not of those who've got the cash and those who don't, but of those who've got the cash insofar as you count what's owed to them and those who've got the cash in hand provided they pay it back in double, triple, on and on.

Into such a stalemate walks the melodrama, with all its nervous, pacing energy, its failed attempts to play it cool. Like all good political art, it doesn't know more than the situation it takes on: at most, it performs what cannot not be the case. Those British Gothic scenery chewing Gothic melodramas, those Sirk weepies, this Petri defaulted credit thing that may not look like a melodrama, but that is one at the end of the day, all the more because it registers the sense that neither the expected structure nor the emergency measures of pushing your buttons is going to channel the affects of the viewers correctly: all these melodramas are a lost didactic mode.

They're part and parcel of something we think of closer to film that wears its politics on its sleeves – Russian kinotrains showing Eisenstein films, Pontecorvo showing the French how the Algerians were busy undoing colonial rule – because what they do is point a finger and say:

see this, this future that is to come? That isn't the present, in some allegory. That is the present insofar as there is no present now that isn't valued in terms of what it might come to mean, a weak approximation of the future garbed in silicone sheen and dark glasses, a version that belongs only to a present that teeters on a razor's edge of future payback, and which has been teetering there for a long time, going nowhere, displacing its mass violence, making more of the same, buying it on credit, playing games, fucking around.

Who can blame such a disaster for at least wanting to look sharp?

1 comment:

I stopped reading once the spoilers started kicking in but I'll definitely check this film out. It sounds a bit like Altman's Quintet. Thanks for the tip.

Post a Comment